Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J. Microbiol > Ahead of print > Article

-

Review

The rise and future of peptide-based antimicrobials - Hyo Jung Kim*

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71150/jm.2510002

Published online: January 30, 2026

College of Pharmacy, Woosuk University, Wanju 55338, Republic of Korea

- *Correspondence Hyo Jung Kim hyojungkim@woosuk.ac.kr

© The Microbiological Society of Korea

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 34 Views

- 3 Download

- ABSTRACT

- Introduction

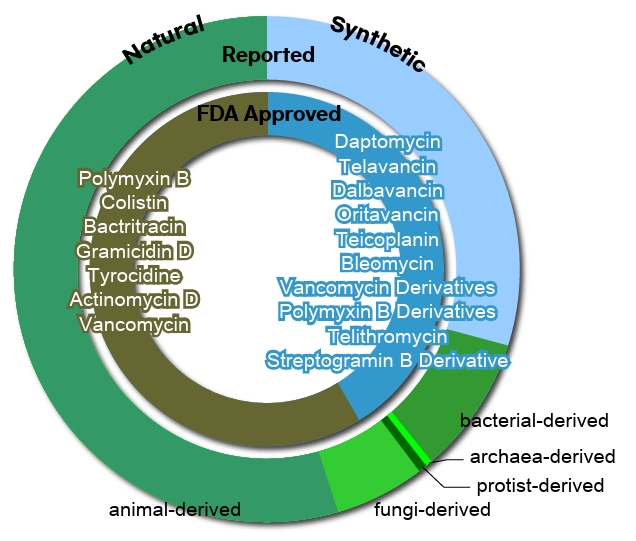

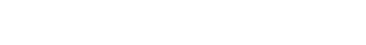

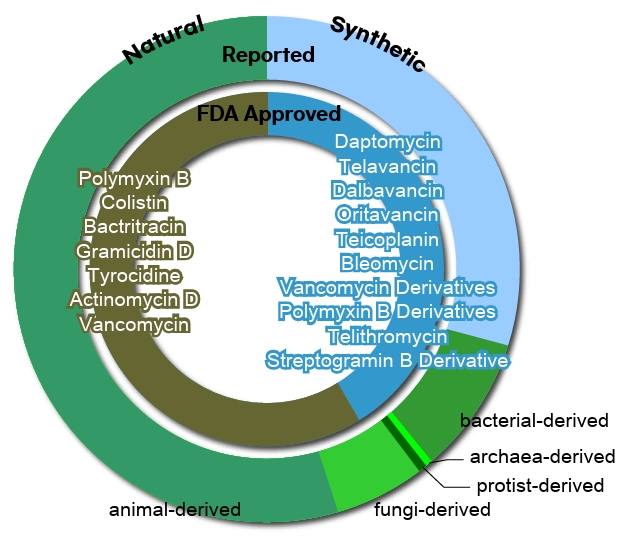

- Origin-based Classification of Peptide Antibiotics

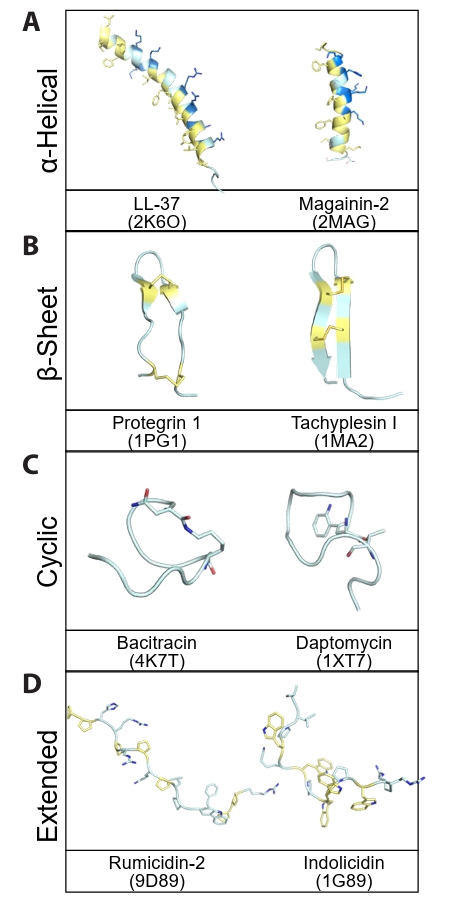

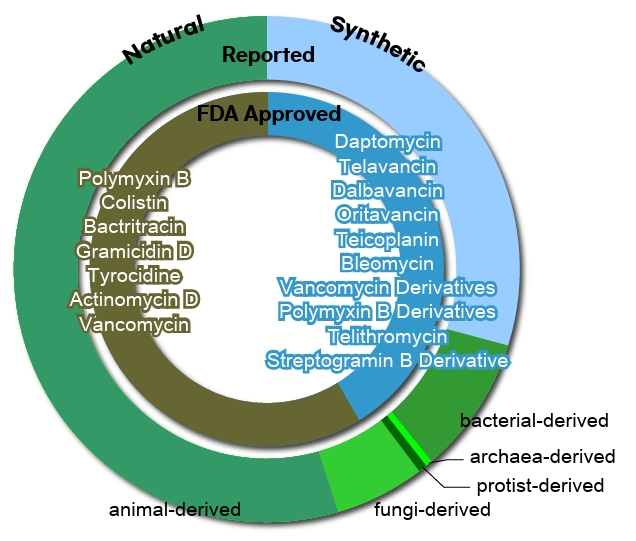

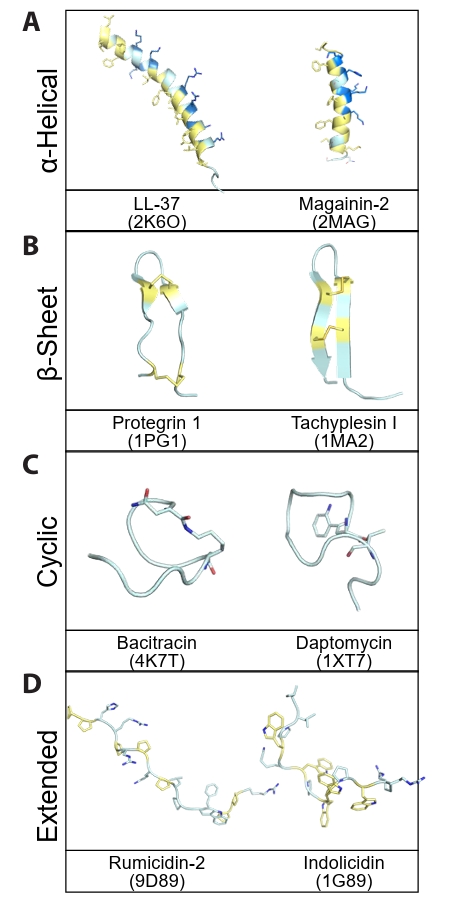

- Structure-based Classification of Peptide Antibiotics

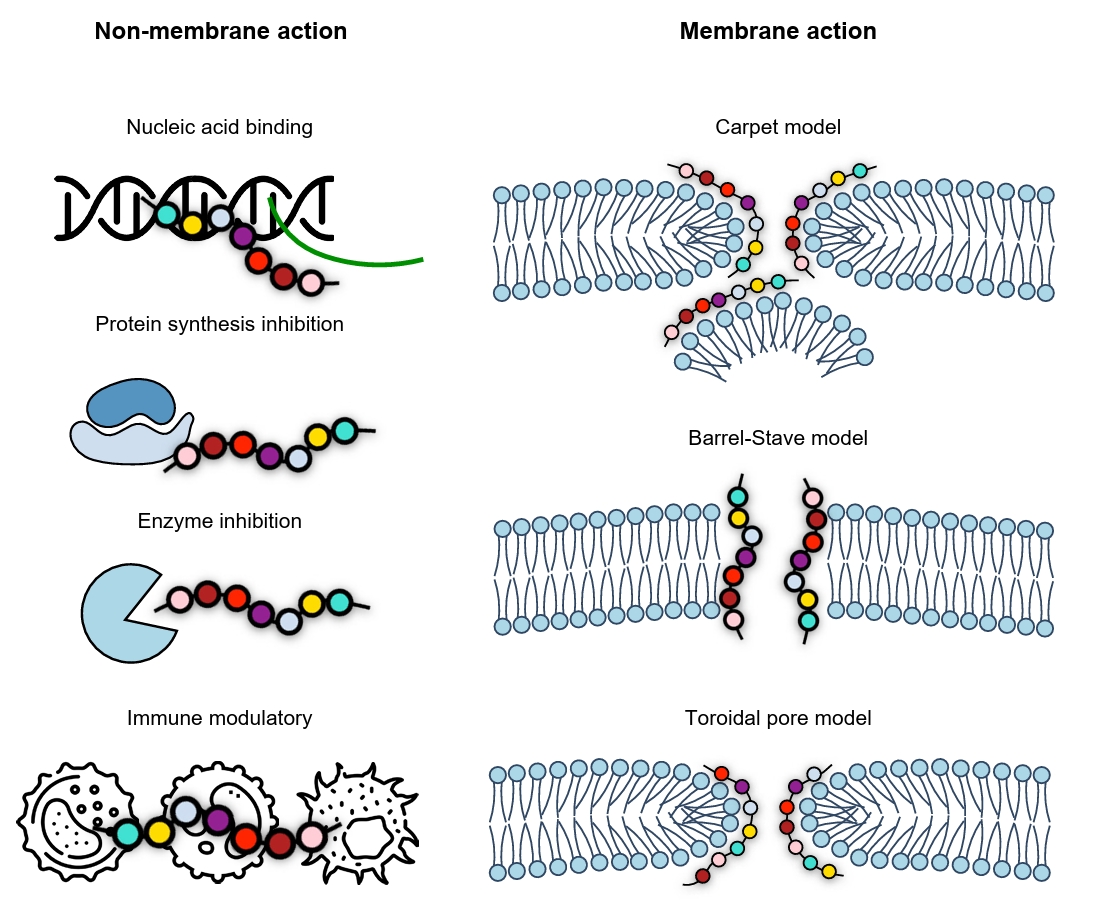

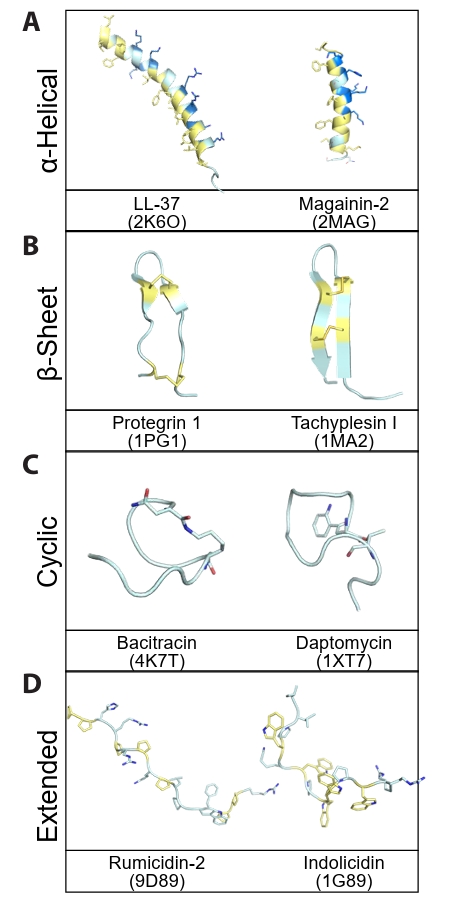

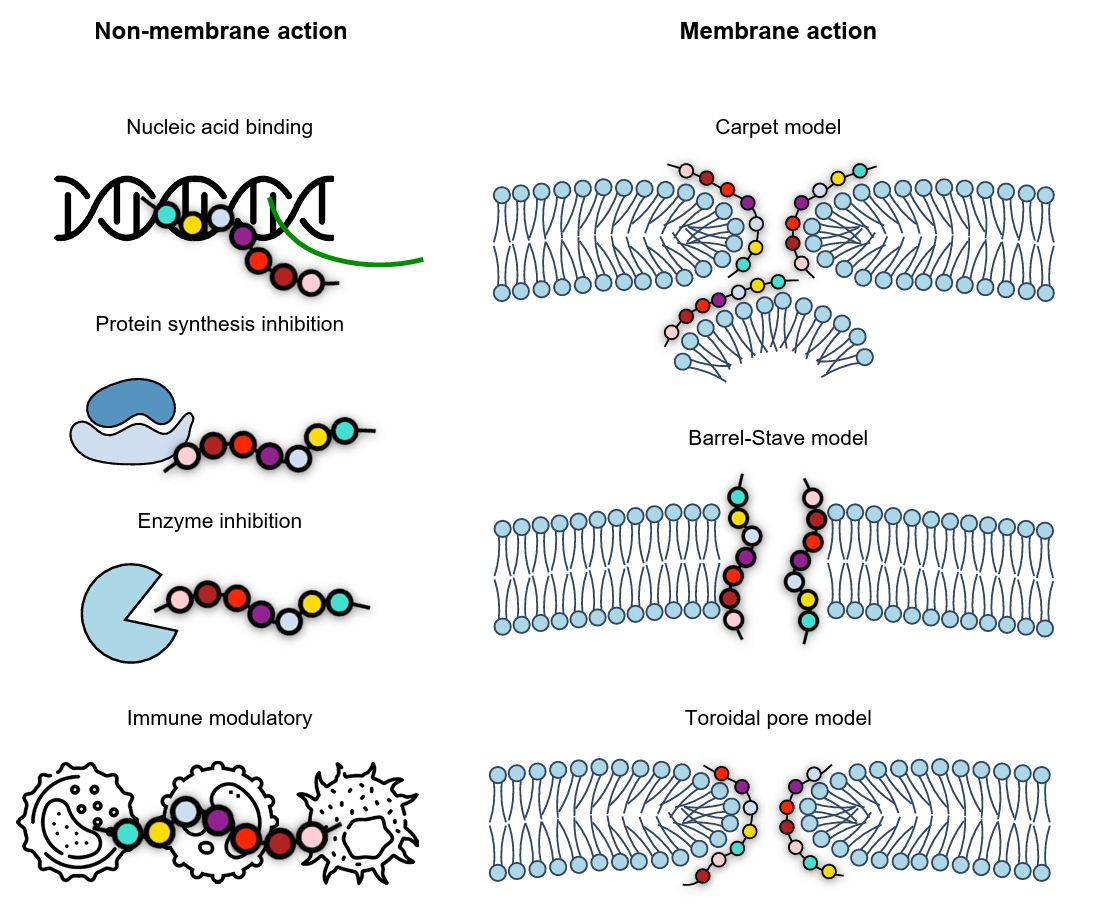

- Mechanism-based Classification of Peptide Antibiotics

- AI-Driven Design and Molecular Optimization Strategies for Peptide Antibiotics

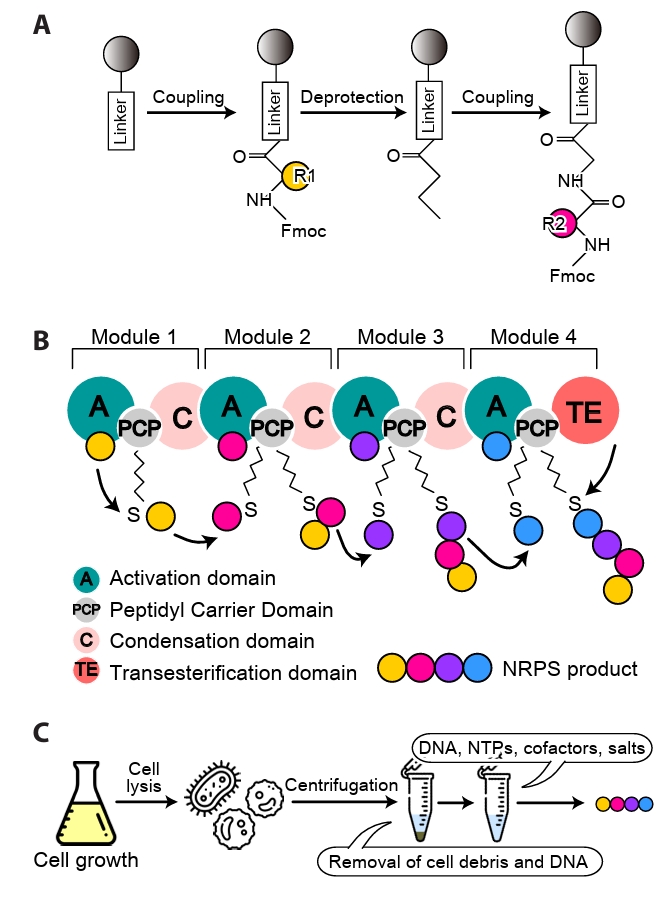

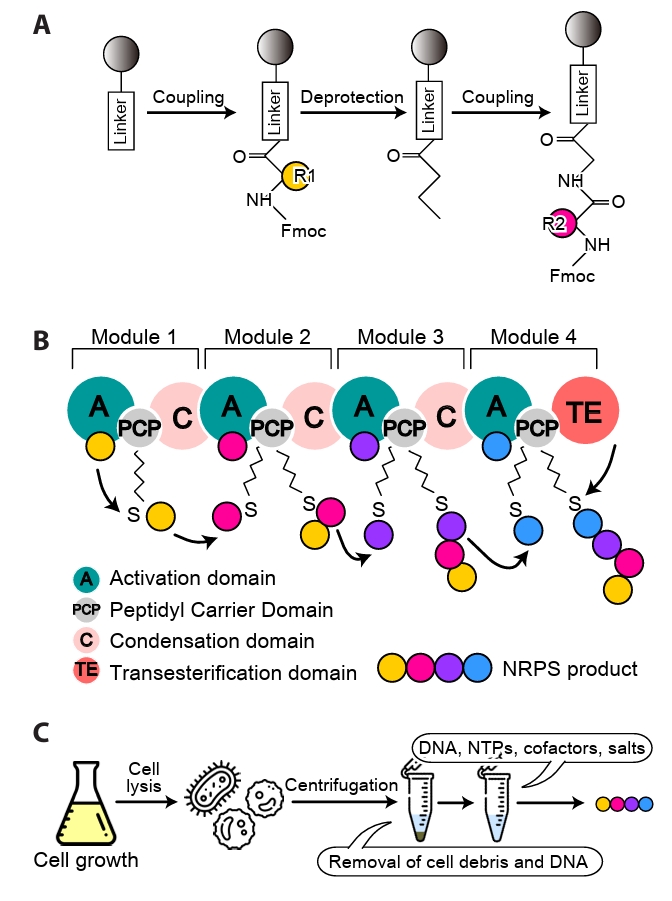

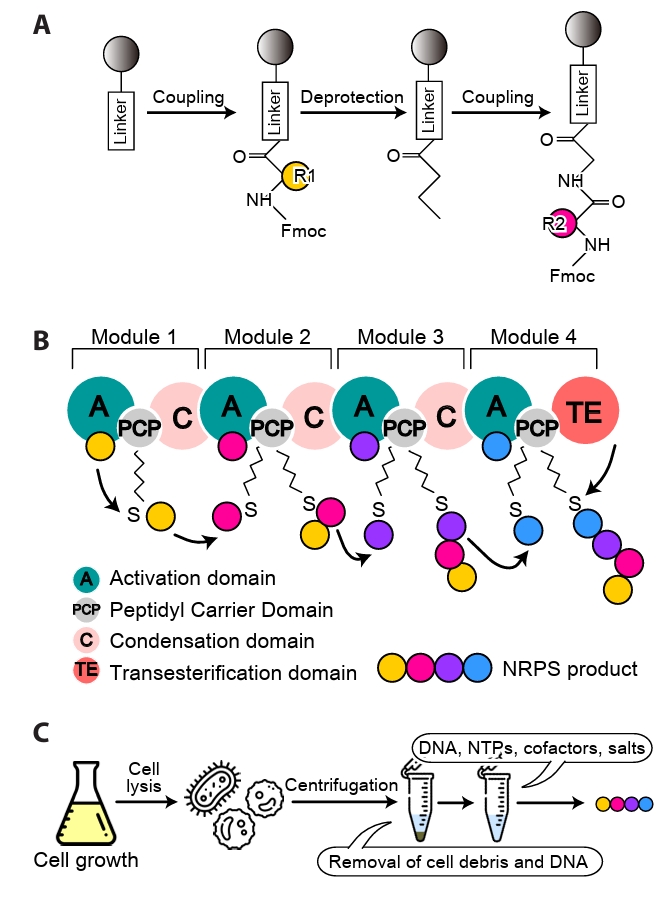

- Synthetic Biology and Manufacturing Strategies

- Delivery Systems and Strategies to Enhance In Vivo Stability

- Clinical Trials and Commercialization Prospects

- Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

- Notes

- References

ABSTRACT

- The escalating threat of antimicrobial resistance has renewed global interest in peptide-based antibiotics as adaptable and effective alternatives to conventional small molecules. Peptides possess diverse mechanisms of action, high target specificity, and structural flexibility, which collectively limit the emergence of resistance. This review outlines recent advances spanning the discovery, optimization, and application of peptide antibiotics, from their biological origins and structural classifications to emerging strategies involving artificial intelligence, synthetic biology, and modern delivery technologies. Peptide antibiotics can be categorized by origin as natural, semi-synthetic, or fully synthetic, and further organized by structural class such as α-helical, β-sheet, cyclic, and extended forms. They are also grouped by function into membrane-targeted and non-membrane-targeted types. These classification schemes are not only descriptive but also critical for understanding the therapeutic potential of peptides, as each category presents distinct advantages and engineering challenges that influence stability, specificity, and overall clinical performance. Advances in artificial intelligence, synthetic biology, and continuous manufacturing are reshaping how peptide drugs are designed and produced, while innovations in drug delivery systems are addressing critical issues of stability and bioavailability. Together, these developments are laying the foundation for a new generation of peptide-based therapeutics capable of meeting the evolving challenges of antimicrobial resistance.

Introduction

Origin-based Classification of Peptide Antibiotics

Structure-based Classification of Peptide Antibiotics

Mechanism-based Classification of Peptide Antibiotics

AI-Driven Design and Molecular Optimization Strategies for Peptide Antibiotics

Synthetic Biology and Manufacturing Strategies

Delivery Systems and Strategies to Enhance In Vivo Stability

Clinical Trials and Commercialization Prospects

Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the members of the Microbiological Society of Korea for their valuable discussions and critical reading of the manuscript, and also appreciates the constructive suggestions that helped improve the clarity of this review. This research was supported by the Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE) program through the Jeonbuk RISE Center, funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Jeonbuk State, Republic of Korea (2025-RISE-13-WSU). This paper was also supported by Woosuk University.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

- Alanjary M, Cano-Prieto C, Gross H, Medema MH. 2019. Computer-aided re-engineering of nonribosomal peptide and polyketide biosynthetic assembly lines. Nat Prod Rep. 36: 1249–1261. ArticlePubMed

- Antoniou AI, Giofre S, Seneci P, Passarella D, Pellegrino S. 2021. Stimulus-responsive liposomes for biomedical applications. Drug Discov Today. 26: 1794–1824. ArticlePubMed

- Ball LJ, Goult CM, Donarski JA, Micklefield J, Ramesh V. 2004. NMR structure determination and calcium binding effects of lipopeptide antibiotic daptomycin. Org Biomol Chem. 2: 1872–1878. ArticlePubMed

- Banhos Danneskiold-Samsøe N, Kavi D, Jude KM, Nissen SB, Wat LW, et al. 2024. AlphaFold2 enables accurate deorphanization of ligands to single-pass receptors. Cell Syst. 15: 1046–1060. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Baral KC, Choi KY. 2025. Barriers and strategies for oral peptide and protein therapeutics delivery: update on clinical advances. Pharmaceutics. 17: 397.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Bucataru C, Ciobanasu C. 2024. Antimicrobial peptides: opportunities and challenges in overcoming resistance. Microbiol Res. 286: 127822.ArticlePubMed

- Cafiso V, Bertuccio T, Spina D, Purrello S, Campanile F, et al. 2012. Modulating activity of vancomycin and daptomycin on the expression of autolysis cell-wall turnover and membrane charge genes in hVISA and VISA strains. PLoS One. 7: e29573. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Camus A, Gantz M, Hilvert D. 2023. High-throughput engineering of nonribosomal extension modules. ACS Chem Biol. 18: 2516–2523. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Cao L, Do T, Link AJ. 2021. Mechanisms of action of ribosomally synthesized and posttranslationally modified peptides (RiPPs). J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 48: kuab005.ArticlePDF

- Chen WW, Chao YJ, Chang WH, Chan JF, Hsu YH. 2018. phosphatidylglycerol incorporates into cardiolipin to improve mitochondrial activity and inhibits inflammation. Sci Rep. 8: 4919.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Chen H, Zhong L, Zhou H, Bai X, Sun T, et al. 2023. Biosynthesis and engineering of the nonribosomal peptides with a C-terminal putrescine. Nat Commun. 14: 6619.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Dassonville-Klimpt A, Sonnet P. 2020. Advances in 'Trojan horse' strategies in antibiotic delivery systems. Future Med Chem. 12: 983–986. ArticlePubMed

- Dathe M, Nikolenko H, Meyer J, Beyermann M, Bienert M. 2001. Optimization of the antimicrobial activity of magainin peptides by modification of charge. FEBS Lett. 501: 146–150. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Dean TT, Jelu-Reyes J, Allen AC, Moore TW. 2024. Peptide-drug conjugates: an emerging direction for the next generation of peptide therapeutics. J Med Chem. 67: 1641–1661. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Doerr S, Majewski M, Perez A, Kramer A, Clementi C, et al. 2021. TorchMD: a deep learning framework for molecular simulations. J Chem Theory Comput. 17: 2355–2363. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Dong R, Liu R, Liu Z, Liu Y, Zhao G, et al. 2025a. Exploring the repository of de novo-designed bifunctional antimicrobial peptides through deep learning. eLife. 13: RP97330.Article

- Dong S, Yu H, Poupart P, Ho EA. 2025b. Gaussian processes modeling for the prediction of polymeric nanoparticle formulation design to enhance encapsulation efficiency and therapeutic efficacy. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 15: 372–388. ArticlePDF

- Eastman P, Galvelis R, Pelaez RP, Abreu CRA, Farr SE, et al. 2024. OpenMM 8: Molecular Dynamics Simulation with Machine Learning Potentials. J Phys Chem B. 128: 109–116. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Economou NJ, Cocklin S, Loll PJ. 2013. High-resolution crystal structure reveals molecular details of target recognition by bacitracin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 110: 14207–14212. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Ehrlich P. 1913. Address in pathology, on chemiotherapy: delivered before the seventeenth international congress of medicine. Br Med J. 2: 353–359. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Esmaeilpour D, Ghomi M, Zare EN, Sillanpaa M. 2025. Nanotechnology-enhanced siRNA delivery: revolutionizing cancer therapy. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 8: 4549–4579. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Fahrner RL, Dieckmann T, Harwig SS, Lehrer RI, Eisenberg D, et al. 1996. Solution structure of protegrin-1, a broad-spectrum antimicrobial peptide from porcine leukocytes. Chem Biol. 3: 543–550. ArticlePubMed

- Fang Y, Jiang Y, Wei L, Ma Q, Ren Z, et al. 2023. DeepProSite: structure-aware protein binding site prediction using ESMFold and pretrained language model. Bioinformatics. 39: btad718.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Fiore M, Alfieri A, Fiore D, Iuliano P, Spatola FG, et al. 2025. Use of daptomycin to manage severe MRSA infections in humans. Antibiotics (Basel). 14: 617.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Fjell CD, Hiss JA, Hancock RE, Schneider G. 2011. Designing antimicrobial peptides: form follows function. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 11: 37–51. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Gao XJ, Ciura K, Ma Y, Mikolajczyk A, Jagiello K, et al. 2024. toward the integration of machine learning and molecular modeling for designing drug delivery nanocarriers. Adv Mater. 36: 2407793.Article

- Gesell J, Zasloff M, Opella SJ. 1997. Two-dimensional 1H NMR experiments show that the 23-residue magainin antibiotic peptide is an α-helix in dodecylphosphocholine micelles, sodium dodecylsulfate micelles, and trifluoroethanol/water solution. J Biomol NMR. 9: 127–135. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Giacomini E, Perrone V, Alessandrini D, Paoli D, Nappi C, et al. 2021. Evidence of antibiotic resistance from population-based studies: a narrative review. Infect Drug Resist. 14: 849–858. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Goldbeck O, Desef DN, Ovchinnikov KV, Perez-Garcia F, Christmann J, et al. 2021. Establishing recombinant production of pediocin PA-1 in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Metab Eng. 68: 34–45. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Guo L, Wang C, Broos J, Kuipers OP. 2023. Lipidated variants of the antimicrobial peptide nisin produced via incorporation of methionine analogs for click chemistry show improved bioactivity. J Biol Chem. 299: 104845.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Han Y, Zhang M, Lai R, Zhang Z. 2021. Chemical modifications to increase the therapeutic potential of antimicrobial peptides. Peptides. 146: 170666.ArticlePubMed

- Hancock RE, Nijnik A, Philpott DJ. 2012. Modulating immunity as a therapy for bacterial infections. Nat Rev Microbiol. 10: 243–254. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Huang DB, Brothers KM, Mandell JB, Taguchi M, Alexander PG, et al. 2022. Engineered peptide PLG0206 overcomes limitations of a challenging antimicrobial drug class. PLoS One. 17: e0274815. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Jiang X, Patil NA, Azad MAK, Wickremasinghe H, Yu H, et al. 2021. A novel chemical biology and computational approach to expedite the discovery of new-generation polymyxins against life-threatening Acinetobacter baumannii. Chem Sci. 12: 12211–12220. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Jin S, Zeng Z, Xiong X, Huang B, Tang L, et al. 2025. AMPGen: an evolutionary information-reserved and diffusion-driven generative model for de novo design of antimicrobial peptides. Commun Biol. 8: 839.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Figurnov M, et al. 2021. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 596: 583–589. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Koehbach J, Muratspahic E, Ahmed ZM, White AM, Tomasevic N, et al. 2024. Chemical synthesis of grafted cyclotides using a "plug and play" approach. RSC Chem Biol. 5: 567–571. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Krizsan A, Volke D, Weinert S, Strater N, Knappe D, et al. 2014. Insect-derived proline-rich antimicrobial peptides kill bacteria by inhibiting bacterial protein translation at the 70S ribosome. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 53: 12236–12239. ArticlePubMed

- Laederach A, Andreotti AH, Fulton DB. 2002. Solution and micelle-bound structures of tachyplesin I and its active aromatic linear derivatives. Biochemistry. 41: 12359–12368. ArticlePubMed

- Li F, Chen J, Leier A, Marquez-Lago T, Liu Q, et al. 2020a. DeepCleave: a deep learning predictor for caspase and matrix metalloprotease substrates and cleavage sites. Bioinformatics. 36: 1057–1065. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Li F, Leier A, Liu Q, Wang Y, Xiang D, et al. 2020b. Procleave: predicting protease-specific substrate cleavage sites by combining sequence and structural information. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 18: 52–64. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Li X, Sabol AL, Wierzbicki M, Salveson PJ, Nowick JS. 2021. An improved turn structure for inducing beta-hairpin formation in peptides. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 60: 22776–22782. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Lin Z, Akin H, Rao R, Hie B, Zhu Z, et al. 2023a. Evolutionary-scale prediction of atomic-level protein structure with a language model. Science. 379: 1123–1130. Article

- Lin TT, Yang LY, Lin CY, Wang CT, Lai CW, et al. 2023b. Intelligent de novo design of novel antimicrobial peptides against antibiotic-resistant bacteria strains. Int J Mol Sci. 24: 6788.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Lu J, Xu H, Xia J, Ma J, Xu J, et al. 2020. D- and unnatural amino acid substituted antimicrobial peptides with improved proteolytic resistance and their proteolytic degradation characteristics. Front Microbiol. 11: 563030.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Luca C, Felletti S, Lievore G, Buratti A, Vogg S, et al. 2020. From batch to continuous chromatographic purification of a therapeutic peptide through multicolumn countercurrent solvent gradient purification. J Chromatogr A. 1625: 461304.ArticlePubMed

- Mahlapuu M, Hakansson J, Ringstad L, Bjorn C. 2016. Antimicrobial peptides: an emerging category of therapeutic agents. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 6: 194.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Mangoni ML, Shai Y. 2009. Temporins and their synergism against Gram-negative bacteria and in lipopolysaccharide detoxification. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1788: 1610–1619. ArticlePubMed

- Martin-Loeches I, Dale GE, Torres A. 2018. Murepavadin: a new antibiotic class in the pipeline. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 16: 259–268. ArticlePubMed

- McDonald EF, Jones T, Plate L, Meiler J, Gulsevin A. 2023. Benchmarking AlphaFold2 on peptide structure prediction. Structure. 31: 111–119. ArticlePubMed

- Melo MN, Ferre R, Castanho MA. 2009. Antimicrobial peptides: linking partition, activity and high membrane-bound concentrations. Nat Rev Microbiol. 7: 245–250. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Morgan SM, O'Connor P M, Cotter PD, Ross RP, Hill C. 2005. Sequential actions of the two component peptides of the lantibiotic lacticin 3147 explain its antimicrobial activity at nanomolar concentrations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 49: 2606–2611. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Mwangi J, Kamau PM, Thuku RC, Lai R. 2023. Design methods for antimicrobial peptides with improved performance. Zool Res. 44: 1095–1114. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Nang SC, Azad MAK, Velkov T, Zhou QT, Li J. 2021. Rescuing the last-line polymyxins: achievements and challenges. Pharmacol Rev. 73: 679–728. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Pandi A, Adam D, Zare A, Trinh VT, Schaefer SL, et al. 2023. Cell-free biosynthesis combined with deep learning accelerates de novo-development of antimicrobial peptides. Nat Commun. 14: 7197.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Panteleev PV, Pichkur EB, Kruglikov RN, Paleskava A, Shulenina OV, et al. 2024. Rumicidins are a family of mammalian host-defense peptides plugging the 70S ribosome exit tunnel. Nat Commun. 15: 8925.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Ratnayake MS, Hansen MH, Cryle MJ. 2024. Enzyme engineering lets us play with new building blocks in non-ribosomal peptide synthesis. Structure. 32: 520–522. ArticlePubMed

- Rentzsch R, Renard BY. 2015. Docking small peptides remains a great challenge: an assessment using AutoDock Vina. Brief Bioinform. 16: 1045–1056. ArticlePubMed

- Rios AC, Moutinho CG, Pinto FC, Del Fiol FS, Jozala A, et al. 2016. Alternatives to overcoming bacterial resistances: State-of-the-art. Microbiol Res. 191: 51–80. ArticlePubMed

- Rozek A, Friedrich CL, Hancock RE. 2000. Structure of the bovine antimicrobial peptide indolicidin bound to dodecylphosphocholine and sodium dodecyl sulfate micelles. Biochemistry. 39: 15765–15774. ArticlePubMed

- Schmidts A, Ormhoj M, Choi BD, Taylor AO, Bouffard AA, et al. 2019. Rational design of a trimeric APRIL-based CAR-binding domain enables efficient targeting of multiple myeloma. Blood Adv. 3: 3248–3260. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Seefeldt AC, Graf M, Perebaskine N, Nguyen F, Arenz S, et al. 2016. Structure of the mammalian antimicrobial peptide Bac7(1–16) bound within the exit tunnel of a bacterial ribosome. Nucleic Acids Res. 44: 2429–2438. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Shi J, So LY, Chen F, Liang J, Chow HY, et al. 2018. Influences of disulfide connectivity on structure and antimicrobial activity of tachyplesin I. J Pept Sci. 24: e3087. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Sivanesam K, Kier BL, Whedon SD, Chatterjee C, Andersen NH. 2016. Hairpin structure stability plays a role in the activity of two antimicrobial peptides. FEBS Lett. 590: 4480–4488. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Slingerland CJ, Wesseling CMJ, Innocenti P, Westphal KGC, Masereeuw R, et al. 2022. Synthesis and evaluation of polymyxins bearing reductively labile disulfide-linked lipids. J Med Chem. 65: 15878–15892. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Song J, Tan H, Perry AJ, Akutsu T, Webb GI, et al. 2012. PROSPER: an integrated feature-based tool for predicting protease substrate cleavage sites. PLoS One. 7: e50300. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Srinivas N, Jetter P, Ueberbacher BJ, Werneburg M, Zerbe K, et al. 2010. Peptidomimetic antibiotics target outer-membrane biogenesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Science. 327: 1010–1013. ArticlePubMed

- Strebhardt K, Ullrich A. 2008. Paul Ehrlich's magic bullet concept: 100 years of progress. Nat Rev Cancer. 8: 473–480. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Strieker M, Tanovic A, Marahiel MA. 2010. Nonribosomal peptide synthetases: structures and dynamics. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 20: 234–240. ArticlePubMed

- Szymczak P, Szczurek E. 2023. Artificial intelligence-driven antimicrobial peptide discovery. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 83: 102733.ArticlePubMed

- Tan HN, Liu WQ, Ho J, Chen YJ, Shieh FJ, et al. 2024. Structure prediction and protein engineering yield new insights into Microcin J25 precursor recognition. ACS Chem Biol. 19: 1982–1990. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Taylor SD, Moreira R. 2025. Daptomycin: mechanism of action, mechanisms of resistance, synthesis and structure-activity relationships. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 212: 163–234. ArticlePubMed

- Torres MDT, Chen LT, Wan F, Chatterjee P, de la Fuente-Nunez C. 2025. Generative latent diffusion language modeling yields anti-infective synthetic peptides. Cell Biomaterials. 1: 100183.Article

- Uddin TM, Chakraborty AJ, Khusro A, Zidan BRM, Mitra S, et al. 2021. Antibiotic resistance in microbes: History, mechanisms, therapeutic strategies and future prospects. J Infect Public Health. 14: 1750–1766. ArticlePubMed

- Verma S, Goand UK, Husain A, Katekar RA, Garg R, et al. 2021. Challenges of peptide and protein drug delivery by oral route: current strategies to improve the bioavailability. Drug Dev Res. 82: 927–944. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Vrbnjak K, Sewduth RN. 2024. Recent advances in peptide drug discovery: novel strategies and targeted protein degradation. Pharmaceutics. 16: 1486.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Walensky LD, Bird GH. 2014. Hydrocarbon-stapled peptides: principles, practice, and progress. J Med Chem. 57: 6275–6288. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Wang G. 2008. Structures of human host defense cathelicidin LL-37 and its smallest antimicrobial peptide KR-12 in lipid micelles. J Biol Chem. 283: 32637–32643. ArticlePubMed

- Wang J, Feng J, Kang Y, Pan P, Ge J, et al. 2025a. Discovery of antimicrobial peptides with notable antibacterial potency by an LLM-based foundation model. Sci Adv. 11: eads8932.Article

- Wang G, Schmidt C, Li X, Wang Z. 2025b. APD6: the antimicrobial peptide database is expanded to promote research and development by deploying an unprecedented information pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 10: gkaf860.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Wang Y, Song M, Liu F, Liang Z, Hong R, et al. 2025c. Artificial intelligence using a latent diffusion model enables the generation of diverse and potent antimicrobial peptides. Sci Adv. 11: eadp7171. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Wang XF, Tang JY, Sun J, Dorje S, Sun TQ, et al. 2024. ProT-Diff: a modularized and efficient strategy for de novo generation of antimicrobial peptide sequences by integrating protein language and diffusion models. Adv Sci (Weinh). 11: e2406305. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Wenski SL, Thiengmag S, Helfrich EJN. 2022. Complex peptide natural products: biosynthetic principles, challenges and opportunities for pathway engineering. Synth Syst Biotechnol. 7: 631–647. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Wenzler E, Rodvold KA. 2015. Telavancin: the long and winding road from discovery to food and drug administration approvals and future directions. Clin Infect Dis. 61: S38–S47. ArticlePubMed

- Wu J, Sahoo JK, Li Y, Xu Q, Kaplan DL. 2022. Challenges in delivering therapeutic peptides and proteins: A silk-based solution. J Control Release. 345: 176–189. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Yan J, Cai J, Zhang B, Wang Y, Wong DF, et al. 2022. Recent progress in the discovery and design of antimicrobial peptides using traditional machine learning and deep learning. Antibiotics (Basel). 11: 1451.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Yi H, Raman AT, Zhang H, Allen GI, Liu Z. 2018. Detecting hidden batch factors through data-adaptive adjustment for biological effects. Bioinformatics. 34: 1141–1147. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Zhang P, Li M, Xiao C, Chen X. 2021. Stimuli-responsive polypeptides for controlled drug delivery. Chem Commun (Camb). 57: 9489–9503. ArticlePubMed

- Zhang L, Wang C, Chen K, Zhong W, Xu Y, et al. 2023. Engineering the biosynthesis of fungal nonribosomal peptides. Nat Prod Rep. 40: 62–88. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Zheng B, Wang X, Guo M, Tzeng CM. 2025. Therapeutic peptides: recent advances in discovery, synthesis, and clinical translation. Int J Mol Sci. 26: 5131.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Zhong G, Wang ZJ, Yan F, Zhang Y, Huo L. 2023. Recent advances in discovery, bioengineering, and bioactivity-evaluation of ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides. ACS Bio Med Chem Au. 3: 1–31. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Zhou H, Zhu Y, Yang B, Huo Y, Yin Y, et al. 2024. Stimuli-responsive peptide hydrogels for biomedical applications. J Mater Chem B. 12: 1748–1774. ArticlePubMed

References

Figure & Data

References

Citations

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.

TOP

MSK

MSK

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite this Article

Cite this Article