Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J. Microbiol > Ahead of print > Article

-

Review

Proteostasis-targeted antibacterial strategies - Yoon Chae Jeong1,2,†, Seong-Hyeon Kim1,†, Seongjoon Moon1,†, Hyunhee Kim1,3,*, Changhan Lee1,*

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71150/jm.2511007

Published online: February 12, 2026

1Department of Biological Sciences, Ajou University, Suwon 16499, Republic of Korea

2Ajou Energy Science Research Center, Ajou University, Suwon 16499, Republic of Korea

3Research Institute of Basic Sciences, Ajou University, Suwon 16499, Republic of Korea

- *Correspondence Hyunhee Kim hyunheek@ajou.ac.kr Changhan Lee leec@ajou.ac.kr

- †These authors contributed equally to this work.

© The Microbiological Society of Korea

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 13 Views

- 4 Download

- ABSTRACT

- Introduction

- A Proteostasis-Centered View of Protein Life Cycle

- Antibiotic Effects on Bacterial Proteostasis

- Importance of Chaperones in Antibiotic Effects

- Potentiation of Antibiotics by Chaperone Inhibition

- Aggregation-Prone Peptides (APPs)

- Targeting Proteolysis

- BacPROTAC for Targeted Protein Degradation in Bacteria

- Dormancy and Proteostasis-based Therapeutic Strategies

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

ABSTRACT

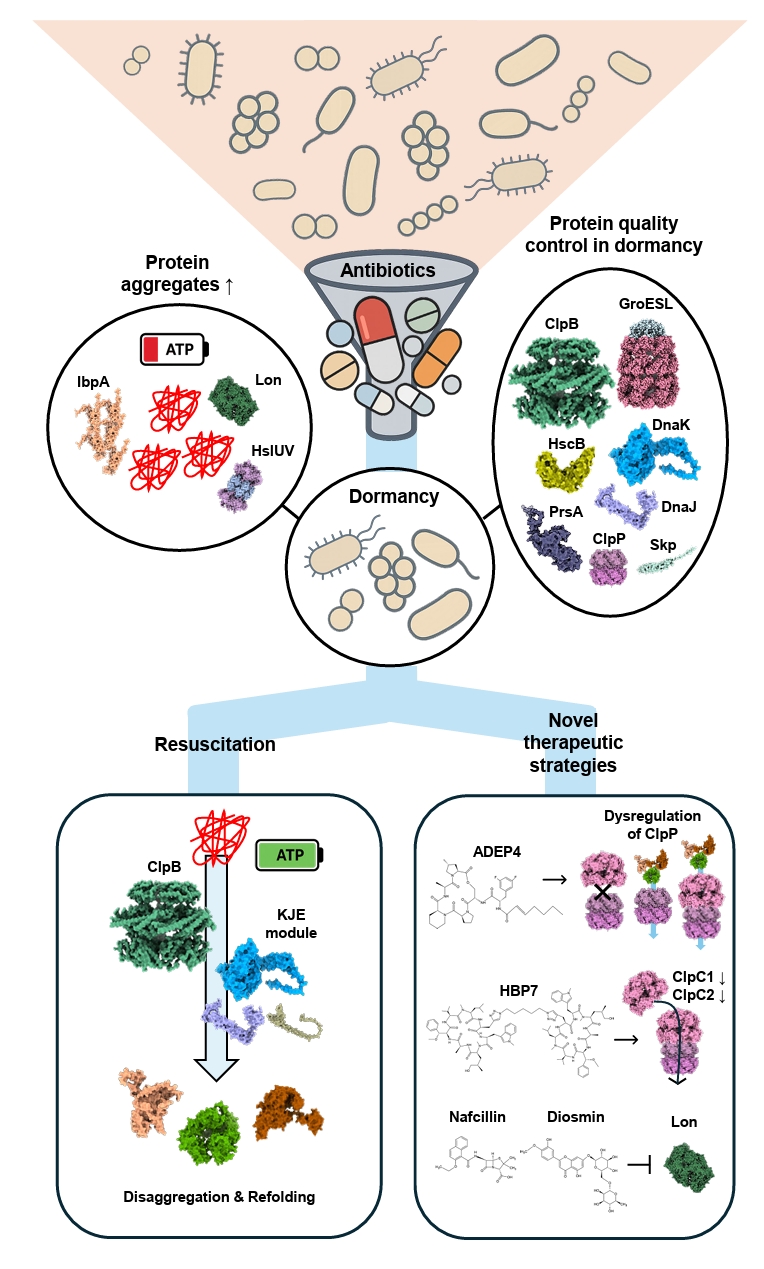

- Protein quality control systems are increasingly recognized as a critical determinant of bacterial survival and antibiotic tolerance. Conventional antibiotics predominantly target nucleic acids, protein synthesis, or cell wall synthesis, yet bacterial adaptation and resistance emergence remain major challenges. Targeting the bacterial protein quality control machineries including molecular chaperones and proteases offers a promising strategy to overcome these limitations. Recent advances include small molecules and adaptor/degron mimetics that modulate the activities of chaperones and proteases, aggregation-prone peptides (APPs) that induce proteotoxic stress, and bacterial PROTAC (BacPROTAC) strategies that redirect endogenous proteases. Notably, persister and viable-but-non-culturable (VBNC) cells, which tolerate conventional antibiotics, remain susceptible to proteostasis-targeted approaches, thereby enabling killing in both actively dividing and dormant populations. Furthermore, synergistic strategies combining chaperone inhibition or protease activation with conventional antibiotics enhance bactericidal efficacy, suggesting a potential avenue to mitigate antimicrobial resistance. This review summarizes the mechanistic basis, recent developments, and translational potential of proteostasis-centered antibacterial strategies.

Introduction

A Proteostasis-Centered View of Protein Life Cycle

Antibiotic Effects on Bacterial Proteostasis

Importance of Chaperones in Antibiotic Effects

Potentiation of Antibiotics by Chaperone Inhibition

Aggregation-Prone Peptides (APPs)

Targeting Proteolysis

BacPROTAC for Targeted Protein Degradation in Bacteria

Dormancy and Proteostasis-based Therapeutic Strategies

Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Changhan Lee received funding from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (grant No. RS-2024-00452071, RS-2025-02313052). Changhan Lee and Yoon Chae Jeong received funding from Learning & Academic research institution for Master’s•PhD students, and Postdocs (LAMP) Program of NRF grant funded by the Ministry of Education (grant No. RS-2023-00285390). Hyunhee Kim received fundings from the MSIT (grant No. RS-2025-24683601) and from the Core Research Institute Basic Science Research Program through the NRF funded by the Ministry of Education (grant No. 2021R1A6A1A10044950).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests exist.

| Annotation in Fig. 1 | Name | Target sites | Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Telaprevir | SBD | Inhibit ATPase and chaperone activities of DnaK by disrupting allosteric coupling via substrate-mimicking interaction with the SBD | Hosfelt et al. (2022) |

| BI-88E3 | SBD | Disrupt allosteric interaction within DnaK | Cellitti et al. (2009) | |

| BI-88D7 | ||||

| BI-88B12 | ||||

| Nα-[Tetradecanoyl-(4-aminomethylbenzoyl)]-l-isoleucine | SBD | Inhibit the DnaK-mediated catalysis of cis/trans isomerization | Liebscher et al. (2007) | |

| Drosocin | SBD and C-terminal region | Inhibit ATPase and chaperone activities of DnaK by disrupting allosteric coupling via substrate-mimicking interaction with the SBD | Kragol et al. (2001); Otvos et al. (2000) | |

| Pyrrhocoricin | ||||

| Apidaecin 1a | ||||

| Bac-7 | SBD | Impair DnaK-mediated refolding of denatured proteins | Zahn et al. (2014) | |

| CHP-105 | Unknown | Synergistic effect with levofloxacin via DnaK inhibition | Credito et al. (2009) | |

| PET-16 | NBD | Bind to ADP-bound DnaK and inhibit DnaK-client interaction | Leu et al. (2014) | |

| 2 | Compound 8 | Unknown | Bactericidal activity against Escherichia coli | (Abdeen et al. (2016) |

| Compound 18 | ||||

| Hydroxquinolines | Unknown | Inhibit GroEL/ES activity by binding to the apical domain via a noncanonical, non-hydrophobic interaction | Stevens et al. (2020) | |

| Nifuroxazide | Apical domain | Inhibit the GroEL/ES folding cycle through apical domain binding | ||

| Bis-sulfonamido-2-phenylbenzoxazole | Apical domain | Inhibit ring-ring interaction of GroEL, compound derived from sulfonamido-2-arylbenzoxazole | Godek et al. (2024) | |

| Mizoribine | Equatorial domain | Inhibit ATPase activity of GroEL | Itoh et al. (1999) | |

| 3 | BX-2819 | N-terminal domain (NTD) | Inhibit ATPase activity of HtpG | Carlson et al. (2024) |

| HS-291 | BX-2819 derivative binds N-terminal ATP-binding pocket of HtpG, light-activated, triggers ROS generation | |||

| Polymixn B | Inhibit HtpG chaperone function without affecting its ATPase activity | Minagawa et al. (2011) | ||

| 4 | Cu2+-anthracenyl terpyridine complex | FKBP domain | Inhibit SlyD PPIase activity | Kumar and Balbach (2017) |

| 5 | β-Lactone | Active site serine in ClpP | Form covalent bond with the catalytic serine of ClpP and inhibit its proteolytic activity | Böttcher and Sieber (2008) |

| Phenyl esters | Xiao et al. (2025) | |||

| Peptide boronic acids | Akopian et al. (2015) | |||

| Clipibicyclene | Culp et al. (2022) | |||

| PCA | G107, V88, I81 in ClpP | Inhibit ClpP proteolytic activity | Li et al. (2025a) | |

| CA | M31, G33 in ClpP | Inhibit ClpP proteolytic activity by binding to active site residues M31 and G33 | ||

| Ameniaspirol | ClpXP, HslUV (ClpYQ) complex | Competitively inhibit ClpXP and HslUV (ClpYQ) | Labana et al. (2021) | |

| CymA | NTD of ClpC1 | Induce formation of large ClpC1 supercomplexes and activate associated ClpP protease via N-terminal domain binding | Taylor et al. (2022); Vasudevan et al. (2013) | |

| Lassomycin | Stimulate ClpC1 ATPase activity while inhibiting associated ClpP proteolytic activity | Gavrish et al. (2014) | ||

| Ecumicin | Stimulate ClpC1 ATPase activity while inhibiting associated ClpP proteolytic activity | Hong et al. (2023); Hosfelt et al. (2022) | ||

| 6 | Nafcillin | Proteolytic active site | Interact with the binding pocket of Lon protease via hydrogen bonding; not reported as antibiotics | Narimisa et al. (2024) |

| Diosmin | ||||

| MG262 | Form covalent bond with catalytic serine of Lon protease and inhibit its proteolytic activity | Frase and Lee (2007) | ||

| Molecule 11 | Unknown | Inhibition of Lon protease proteolytic activity | Babin et al. (2019) | |

| 7 | ACP | Apical pocket | Enhance ClpP proteolytic activity independent of ATPase | Barghash et al. (2025); Leung et al. (2011) |

| ADEP | Junction of the ClpP subunits | Bind to ClpP tetradecamer and enhance its proteolytic activity | Gersch et al. (2015) |

| Chaperone target | Representative inhibitors | Antibiotic partners | Model organism(s) | Reported effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DnaK/Hsp70 | Telaprevir (HCV protease inhibitor, repurposed) | Kanamycin, Streptomycin, Rifampicin | M. smegmatis, M. tuberculosis | Lowered MIC50 of aminoglycosides; reduced rifampicin resistance frequency; enhanced growth inhibition under heat/proteotoxic stress | Hosfelt et al. (2022) |

| DnaK/Hsp70 | Proline-rich antimicrobial peptides (PrAMPs; e.g., pyrrhocoricin, synthetic dimers) | β-Lactams, Quinolones | E. coli, Salmonella spp. | Synergistic killing via disruption of DnaK folding function; accumulation of proteotoxic stress | Kragol et al. (2001) |

| GroEL/ES | Hydroxybiphenylamide derivatives | Aminoglycosides (e.g., gentamicin) | Staphylococcus aureus | Impaired folding capacity; reduced biofilm survival; enhanced aminoglycoside bactericidal activity | Kunkle et al. (2018) |

| Peptide ID | Target bacteria | Sequence feature | Aggregation morphology | Mammalian toxicity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C30 | MRSA | APR* + Arg flanks | Amyloid-like | Low | Bednarska et al. (2016) |

| C29 | MRSA | APR + Arg flanks | Amyloid-like | Low | |

| Hit50 | MRSA | APR + Arg flanks | Amorphous inclusion bodies | Low | |

| Multiple APRs (263 tested) | S. aureus, E. faecalis, MRSA, Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus | Tandem APR repeats, charged gatekeepers | Amyloid and amorphous aggregation | Low | Khodaparast et al. (2018) |

- Abdeen S, Kunkle T, Salim N, Ray AM, Mammadova N, et al. 2018. Sulfonamido-2-arylbenzoxazole GroEL/ES inhibitors as potent antibacterials against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). J Med Chem. 61: 7345–7357. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Abdeen S, Salim N, Mammadova N, Summers CM, Frankson R, et al. 2016. GroEL/ES inhibitors as potential antibiotics. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 26: 3127–3134. ArticlePubMed

- Aguzzi A, Rajendran L. 2009. The transcellular spread of cytosolic amyloids, prions, and prionoids. Neuron. 64: 783–790. ArticlePubMed

- Akopian T, Kandror O, Tsu C, Lai JH, Wu W, et al. 2015. Cleavage specificity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis ClpP1P2 protease and identification of novel peptide substrates and boronate inhibitors with antibacterial activity. J Biol Chem. 290: 11008–11020. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Almutairy B. 2024. Extensively and multidrug-resistant bacterial strains: case studies of antibiotic resistance. Front Microbiol. 15: 1381511.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Babin BM, Kasperkiewicz P, Janiszewski T, Yoo E, Drag M, et al. 2019. Leveraging peptide substrate libraries to design inhibitors of bacterial Lon protease. ACS Chem Biol. 14: 2453–2462. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Balch WE, Morimoto RI, Dillin A, Kelly JW. 2008. Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science. 319: 916–919. ArticlePubMed

- Balchin D, Hayer-Hartl M, Hartl FU. 2016. In vivo aspects of protein folding and quality control. Science. 353: aac4354.ArticlePubMed

- Baran A, Kwiatkowska A, Potocki L. 2023. Antibiotics and bacterial resistance—a short story of an endless arms race. Int J Mol Sci. 24: 5777.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Barghash MM, Mabanglo MF, Hoff SE, Brozdnychenko D, Wong KS, et al. 2025. Small molecule dysregulation of ClpP activity via bidirectional allosteric pathways. Structure. 33: 1700–1716. ArticlePubMed

- Bednarska NG, Eldere J, Gallardo R, Ganesan A, Ramakers M, et al. 2016. Protein aggregation as an antibiotic design strategy. Mol Microbiol. 99: 849–865. ArticlePubMedLink

- Belay WY, Getachew M, Tegegne BA, Teffera ZH, Dagne A, et al. 2024. Mechanism of antibacterial resistance, strategies and next-generation antimicrobials to contain antimicrobial resistance: a review. Front Pharmacol. 15: 1444781.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Bharadwaj A, Rastogi A, Pandey S, Gupta S, Sohal JS. 2022. Multidrug-resistant bacteria: their mechanism of action and prophylaxis. BioMed Res Int. 2022: 5419874.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Bohl V, Mogk A. 2024. When the going gets tough, the tough get going—novel bacterial AAA+ disaggregases provide extreme heat resistance. Environ Microbiol. 26: e16677. ArticlePubMed

- Bojanovič K, D’Arrigo I, Long KS. 2017. Global transcriptional responses to osmotic, oxidative, and imipenem stress conditions in Pseudomonas putida. Appl Environ Microbiol. 83: e03236-16.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Böttcher T, Sieber SA. 2008. β-Lactones as privileged structures for the active-site labeling of versatile bacterial enzyme classes. Angew Chem Int Ed. 47: 4600–4603. Article

- Butler MS, Vollmer W, Goodall ECA, Capon RJ, Henderson IR, et al. 2024. A review of antibacterial candidates with new modes of action. ACS Infect Dis. 10: 3440–3474. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Calloni G, Chen T, Schermann SM, Chang H, Genevaux P, et al. 2012. DnaK functions as a central hub in the E. coli chaperone network. Cell Rep. 1: 251–264. ArticlePubMed

- Carlson DL, Kowalewski M, Bodoor K, Lietzan AD, Hughes PF, et al. 2024. Targeting Borrelia burgdorferi HtpG with a berserker molecule, a strategy for anti-microbial development. Cell Chem Biol. 31: 465–476. ArticlePubMed

- Cassaignau AME, Cabrita LD, Christodoulou J. 2020. How does the ribosome fold the proteome? Annu Rev Biochem. 89: 389–415. ArticlePubMed

- Cellitti J, Zhang Z, Wang S, Wu B, Yuan H, et al. 2009. Small molecule DnaK modulators targeting the β-domain. Chem Biol Drug Des. 74: 349–357. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Chiappori F, Fumian M, Milanesi L, Merelli I. 2015. DnaK as antibiotic target: hot spot residues analysis for differential inhibition of the bacterial protein in comparison with the human HSP70. PLoS One. 10: e0124563. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Chinemerem Nwobodo D, Ugwu MC, Oliseloke Anie C, Al-Ouqaili MTS, Chinedu Ikem J, et al. 2022. Antibiotic resistance: the challenges and some emerging strategies for tackling a global menace. Clin Lab Anal. 36: e24655.Article

- Cho E, Kim J, Hur JI, Ryu S, Jeon B. 2024. Pleiotropic cellular responses underlying antibiotic tolerance in Campylobacter jejuni. Front Microbiol. 15: 1493849.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Compton CL, Schmitz KR, Sauer RT, Sello JK. 2013. Antibacterial activity of and resistance to small molecule inhibitors of the ClpP peptidase. ACS Chem Biol. 8: 2669–2677. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Conlon BP, Nakayasu ES, Fleck LE, LaFleur MD, Isabella VM, et al. 2013. Activated ClpP kills persisters and eradicates a chronic biofilm infection. Nature. 503: 365–370. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Credito K, Lin G, Koeth L, Sturgess MA, Appelbaum PC. 2009. Activity of levofloxacin alone and in combination with a DnaK inhibitor against Gram-negative rods, including levofloxacin-resistant strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 53: 814–817. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Culp EJ, Sychantha D, Hobson C, Pawlowski AC, Prehna G, et al. 2022. ClpP inhibitors are produced by a widespread family of bacterial gene clusters. Nat Microbiol. 7: 451–462. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Dalbey RE, Wang P, Van Dijl JM. 2012. Membrane proteases in the bacterial protein secretion and quality control pathway. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 76: 311–330. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Darnowski MG, Lanosky TD, Labana P, Brazeau-Henrie JT, Calvert ND, et al. 2022. Armeniaspirol analogues with more potent Gram-positive antibiotic activity show enhanced inhibition of the ATP-dependent proteases ClpXP and ClpYQ. RSC Med Chem. 13: 436–444. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Dawan J, Ahn J. 2022. Bacterial stress responses as potential targets in overcoming antibiotic resistance. Microorganisms. 10: 1385.ArticlePubMedPMC

- De Baets G, Van Doorn L, Rousseau F, Schymkowitz J. 2015. Increased aggregation is more frequently associated to human disease-associated mutations than to neutral polymorphisms. PLoS Comput Biol. 11: e1004374. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Debnath A, Miyoshi S. 2021. The impact of protease during recovery from viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state in Vibrio cholerae. Microorganisms. 9: 2618.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Deuerling E, Gamerdinger M, Kreft SG. 2019. Chaperone interactions at the ribosome. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 11: a033977.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Dewachter L, Bollen C, Wilmaerts D, Louwagie E, Herpels P, et al. 2021. The dynamic transition of persistence toward the viable but nonculturable state during stationary phase is driven by protein aggregation. mBio. 12: e00703–21. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Edgar T, Boyd SD, Palame MJ. 2008. Sustainability for behaviour change in the fight against antibiotic resistance: a social marketing framework. J Antimicrob Chemother. 63: 230–237. ArticlePubMed

- Espinoza-Chávez RM, Salerno A, Liuzzi A, Ilari A, Milelli A, et al. 2023. Targeted protein degradation for infectious diseases: from basic biology to drug discovery. ACS Bio Med Chem Au. 3: 32–45. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Fang X, Allison KR. 2023. Resuscitation dynamics reveal persister partitioning after antibiotic treatment. Mol Syst Biol. 19: e11320. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Fay A, Philip J, Saha P, Hendrickson RC, Glickman MS, et al. 2021. The DnaK chaperone system buffers the fitness cost of antibiotic resistance mutations in mycobacteria. mBio. 12: e00123-21.ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Fernandez-Escamilla AM, Rousseau F, Schymkowitz J, Serrano L. 2004. Prediction of sequence-dependent and mutational effects on the aggregation of peptides and proteins. Nat Biotechnol. 22: 1302–1306. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Frase H, Hudak J, Lee I. 2006. Identification of the proteasome inhibitor MG262 as a potent ATP-dependent inhibitor of the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium Lon protease. Biochemistry. 45: 8264–8274. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Frase H, Lee I. 2007. Peptidyl boronates inhibit Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium Lon protease by a competitive ATP-dependent mechanism. Biochemistry. 46: 6647–6657. ArticlePubMed

- Ganesan A, Debulpaep M, Wilkinson H, Durme JV, Baets GD, et al. 2015. Selectivity of aggregation-determining interactions. J Mol Biol. 427: 236–247. ArticlePubMed

- Gao W, Kim JY, Anderson JR, Akopian T, Hong S, et al. 2015. The cyclic peptide ecumicin targeting ClpC1 is active against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 59: 880–889. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Gavrish E, Sit CS, Cao S, Kandror O, Spoering A, et al. 2014. Lassomycin, a ribosomally synthesized cyclic peptide, kills Mycobacterium tuberculosis by targeting the ATP-dependent protease ClpC1P1P2. Chem Biol. 21: 509–518. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Gersch M, Famulla K, Dahmen M, Göbl C, Malik I, et al. 2015. AAA+ chaperones and acyldepsipeptides activate the ClpP protease via conformational control. Nat Commun. 6: 6320.ArticlePubMedPDF

- Godek J, Sivinski J, Watson ER, Lebario F, Xu W, et al. 2024. Bis-sulfonamido-2-phenylbenzoxazoles validate the GroES/EL chaperone system as a viable antibiotic target. J Am Chem Soc. 146: 20845–20856. ArticlePubMedLink

- Goldstein BP. 2014. Resistance to rifampicin: a review. J Antibiot. 67: 625–630. ArticlePDF

- Goltermann L, Good L, Bentin T. 2013. Chaperonins fight aminoglycoside-induced protein misfolding and promote short-term tolerance in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 288: 10483–10489. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Goltermann L, Sarusie MV, Bentin T. 2016. Chaperonin GroEL/GroES overexpression promotes aminoglycoside resistance and reduces drug susceptibilities in Escherichia coli following exposure to sublethal aminoglycoside doses. Front Microbiol. 6: 1572.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Gottesman S, Roche E, Zhou Y, Sauer RT. 1998. The ClpXP and ClpAP proteases degrade proteins with carboxy-terminal peptide tails added by the SsrA-tagging system. Genes Dev. 12: 1338–1347. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Guillouzo A, Guguen-Guillouzo C. 2020. Antibiotics-induced oxidative stress. Curr Opin Toxicol. 20–21: 23–28. Article

- Gur E, Vishkautzan M, Sauer RT. 2012. Protein unfolding and degradation by the AAA+ Lon protease. Protein Sci. 21: 268–278. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Halawa EM, Fadel M, Al-Rabia MW, Behairy A, Nouh NA, et al. 2024. Antibiotic action and resistance: updated review of mechanisms, spread, influencing factors, and alternative approaches for combating resistance. Front Pharmacol. 14: 1305294.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Hancock REW, Chapple DS. 1999. Peptide antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 43: 1317–1323. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Harnagel A, Quezada LL, Park SW, Baranowski C, Kieser K, et al. 2021. Nonredundant functions of Mycobacterium tuberculosis chaperones promote survival under stress. Mol Microbiol. 115: 272–289. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Hoi DM, Junker S, Junk L, Schwechel K, Fischel K, et al. 2023. Clp-targeting BacPROTACs impair mycobacterial proteostasis and survival. Cell. 186: 2176–2192. ArticlePubMed

- Hong J, Duc NM, Jeong BC, Cho S, Shetye G, et al. 2023. Identification of the inhibitory mechanism of ecumicin and rufomycin 4-7 on the proteolytic activity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis ClpC1/ClpP1/ClpP2 complex. Tuberculosis. 138: 102298.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Hooper DC. 2001. Mechanisms of action of antimicrobials: focus on fluoroquinolones. Clin Infect Dis. 32: S9–S15. ArticlePubMed

- Hosfelt J, Richards A, Zheng M, Adura C, Nelson B, et al. 2022. An allosteric inhibitor of bacterial Hsp70 chaperone potentiates antibiotics and mitigates resistance. Cell Chem Biol. 29: 854–869. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Itoh H, Komatsuda A, Wakui H, Miura AB, Tashima Y. 1999. Mammalian HSP60 is a major target for an immunosuppressant mizoribine. J Biol Chem. 274: 35147–35151. ArticlePubMed

- Izert-Nowakowska MA, Klimecka MM, Antosiewicz A, Wróblewski K, Kowalski JJ, et al. 2025. Targeted protein degradation in Escherichia coli using CLIPPERs. EMBO Rep. 26: 3994–4016. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Junk L, Schmiedel VM, Guha S, Fischel K, Greb P, et al. 2024. Homo-BacPROTAC-induced degradation of ClpC1 as a strategy against drug-resistant mycobacteria. Nat Commun. 15: 2005.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Kapoor G, Saigal S, Elongavan A. 2017. Action and resistance mechanisms of antibiotics: a guide for clinicians. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 33: 300.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Khodaparast L, Gallardo R, Louros NN, Michiels E, et al. 2018. Aggregating sequences that occur in many proteins constitute weak spots of bacterial proteostasis. Nat Commun. 9: 866.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Khodaparast L, Wu G, Schmidt BZ, Rousseau F, et al. 2021. Bacterial protein homeostasis disruption as a therapeutic intervention. Front Mol Biosci. 8: 681855.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Kirstein J, Hoffmann A, Lilie H, Schmidt R, Rübsamen‐Waigmann H, et al. 2009. The antibiotic ADEP reprogrammes ClpP, switching it from a regulated to an uncontrolled protease. EMBO Mol Med. 1: 37–49. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Klein EY, Impalli I, Poleon S, Denoel P, Cipriano M, et al. 2024. Global trends in antibiotic consumption during 2016-2023 and future projections through 2030. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 121: e2411919121. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Koga H, Kaushik S, Cuervo AM. 2011. Protein homeostasis and aging: the importance of exquisite quality control. Ageing Res Rev. 10: 205–215. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Collins JJ. 2010. How antibiotics kill bacteria: from targets to networks. Nat Rev Microbiol. 8: 423–435. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Wierzbowski J, Cottarel G, Collins JJ. 2008. Mistranslation of membrane proteins and two-component system activation trigger antibiotic-mediated cell death. Cell. 135: 679–690. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Kragol G, Lovas S, Varadi G, Condie BA, Hoffmann R, et al. 2001. The antibacterial peptide pyrrhocoricin inhibits the ATPase actions of DnaK and prevents chaperone-assisted protein folding. Biochemistry. 40: 3016–3026. ArticlePubMed

- Kuhlmann NJ, Chien P. 2017. Selective adaptor dependent protein degradation in bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol. 36: 118–127. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Kumar A, Balbach J. 2017. Targeting the molecular chaperone SlyD to inhibit bacterial growth with a small molecule. Sci Rep. 7: 42141.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Kunkle T, Abdeen S, Salim N, Ray AM, Stevens M, et al. 2018. Hydroxybiphenylamide GroEL/ES inhibitors are potent antibacterials against planktonic and biofilm forms of Staphylococcus aureus. J Med Chem. 61: 10651–10664. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Labana P, Dornan MH, Lafrenière M, Czarny TL, Brown ED, et al. 2021. Armeniaspirols inhibit the AAA+ proteases ClpXP and ClpYQ leading to cell division arrest in Gram-positive bacteria. Cell Chem Biol. 28: 1703–1715. ArticlePubMed

- Lashuel HA, Lansbury PT. 2006. Are amyloid diseases caused by protein aggregates that mimic bacterial pore-forming toxins? Q Rev Biophys. 39: 167–201. ArticlePubMed

- Leu JIJ, Zhang P, Murphy ME, Marmorstein R, George DL. 2014. Structural basis for the inhibition of HSP70 and DnaK chaperones by small-molecule targeting of a C-terminal allosteric pocket. ACS Chem Biol. 9: 2508–2516. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Leung E, Datti A, Cossette M, Goodreid J, McCaw SE, et al. 2011. Activators of cylindrical proteases as antimicrobials: identification and development of small molecule activators of ClpP protease. Chem Biol. 18: 1167–1178. ArticlePubMed

- Li S, Lv H, Zhou Y, Wang J, Deng X, et al. 2025a. Anti-infective therapy of inhibiting Staphylococcus aureus ClpP by protocatechuic aldehyde. Int Immunopharmacol. 157: 114802.Article

- Li S, Zhang Y, Wang J, Lv H, Ma H, et al. 2025b. Discovery of coniferaldehyde as an inhibitor of caseinolytic protease to combat Staphylococcus aureus infections. Mol Med. 31: 249.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Liang J, Tang X, Guo N, Zhang K, Guo A, et al. 2012. Genome-wide expression profiling of the response to linezolid in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Curr Microbiol. 64: 530–538. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Liebscher M, Jahreis G, Lücke C, Grabley S, Raina S, et al. 2007. Fatty acyl benzamido antibacterials based on inhibition of DnaK-catalyzed protein folding. J Biol Chem. 282: 4437–4446. ArticlePubMed

- Ling J, Cho C, Guo LT, Aerni HR, Rinehart J, et al. 2012. Protein aggregation caused by aminoglycoside action is prevented by a hydrogen peroxide scavenger. Mol Cell. 48: 713–722. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Liu S, Huang Y, Jensen S, Laman P, Kramer G, et al. 2024a. Molecular physiological characterization of the dynamics of persister formation in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 68: e00850-23.ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Liu S, Laman P, Jensen S, Van der Wel NN, Kramer G, et al. 2024b. Isolation and characterization of persisters of the pathogenic microorganism Staphylococcus aureus. iScience. 27: 110002.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Lobritz MA, Andrews IW, Braff D, Porter CBM, Gutierrez A, et al. 2022. Increased energy demand from anabolic-catabolic processes drives β-lactam antibiotic lethality. Cell Chem Biol. 29: 276–286. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Lukačišinová M, Fernando B, Bollenbach T. 2020. Highly parallel lab evolution reveals that epistasis can curb the evolution of antibiotic resistance. Nat Commun. 11: 3105.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Mahmoud SA, Chien P. 2018. Regulated proteolysis in bacteria. Annu Rev Biochem. 87: 677–696. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Malik IT, Brötz-Oesterhelt H. 2017. Conformational control of the bacterial Clp protease by natural product antibiotics. Nat Prod Rep. 34: 815–831. ArticlePubMed

- Maurer M, Linder D, Franke KB, Jäger J, Taylor G, et al. 2019. Toxic activation of an AAA+ protease by the antibacterial drug cyclomarin A. Cell Chem Biol. 26: 1169–1179. ArticlePubMed

- Michiels JE, Van den Bergh B, Verstraeten N, Michiels J. 2016. Molecular mechanisms and clinical implications of bacterial persistence. Drug Resist Updat. 29: 76–89. ArticlePubMed

- Minagawa S, Kondoh Y, Sueoka K, Osada H, Nakamoto H. 2011. Cyclic lipopeptide antibiotics bind to the N-terminal domain of the prokaryotic Hsp90 to inhibit the chaperone activity. Biochem J. 435: 237–246. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Mogk A. 1999. Identification of thermolabile Escherichia coli proteins: prevention and reversion of aggregation by DnaK and ClpB. EMBO J. 18: 6934–6949. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Mogk A, Huber D, Bukau B. 2011. Integrating protein homeostasis strategies in prokaryotes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 3: a004366.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Mohiuddin SG, Massahi A, Orman MA. 2022. lon deletion impairs persister cell resuscitation in Escherichia coli. mBio. 13: e02187-21.ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Møller TSB, Liu G, Hartman HB, Rau MH, Mortensen S, et al. 2020. Global responses to oxytetracycline treatment in tetracycline-resistant Escherichia coli. Sci Rep. 10: 8438.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Morales R, Moreno-Gonzalez I, Soto C. 2013. Cross-seeding of misfolded proteins: implications for etiology and pathogenesis of protein misfolding diseases. PLoS Pathog. 9: e1003537. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Morreale FE, Kleine S, Leodolter J, Junker S, Hoi DM, et al. 2022. BacPROTACs mediate targeted protein degradation in bacteria. Cell. 185: 2338–2353.e18. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Narimisa N, Razavi S, Khoshbayan A, Gharaghani S, Jazi FM. 2024. Targeting lon protease to inhibit persister cell formation in Salmonella Typhimurium: a drug repositioning approach. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 14: 1427312.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Nie Q, Wu JWY, Zhang K, Lin SL, Law COR, et al. 2025. SsrA-based design of BacPROTACs for β-lactamase degradation in Gram-negative bacteria. Chem Commun. 61: 13149–13152. Article

- Niu H, Gu J, Zhang Y. 2024. Bacterial persisters: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic development. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 9: 174.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Obuchowski I, Karaś P, Liberek K. 2021. The small ones matter—sHsps in the bacterial chaperone network. Front Mol Biosci. 8: 666893.ArticlePubMedPMC

- O’Rourke A, Beyhan S, Choi Y, Morales P, Chan AP, et al. 2020. Mechanism-of-action classification of antibiotics by global transcriptome profiling. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 64: e01207-19.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Otvos L, O I, Rogers ME, Consolvo PJ, Condie BA, et al. 2000. Interaction between heat shock proteins and antimicrobial peptides. Biochemistry. 39: 14150–14159. ArticlePubMed

- Petkov R, Camp AH, Isaacson RL, Torpey JH. 2023. Targeting bacterial degradation machinery as an antibacterial strategy. Biochem J. 480: 1719–1731. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Pu Y, Li Y, Jin X, Tian T, Ma Q, et al. 2019. ATP-dependent dynamic protein aggregation regulates bacterial dormancy depth critical for antibiotic tolerance. Mol Cell. 73: 143–156. ArticlePubMed

- Pytel D, Fromm Longo J. 2025. The proteostasis network in proteinopathies. Am J Pathol. 195: 1998–2014. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Radzikowski JL, Vedelaar S, Siegel D, Ortega AD, Schmidt A, et al. 2016. Bacterial persistence is an active σS stress response to metabolic flux limitation. Mol Syst Biol. 12: 882.ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Reinhardt L, Thomy D, Lakemeyer M, Westermann LM, Ortega J, et al. 2022. Antibiotic acyldepsipeptides stimulate the Streptomyces Clp-ATPase/ClpP complex for accelerated proteolysis. mBio. 13: e01413-22.ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Richards A, Lupoli TJ. 2023. Peptide-based molecules for the disruption of bacterial Hsp70 chaperones. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 76: 102373.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Rosenzweig R, Moradi S, Zarrine-Afsar A, Glover JR, Kay LE. 2013. Unraveling the mechanism of protein disaggregation through a ClpB-DnaK interaction. Science. 339: 1080–1083. ArticlePubMed

- Rousseau F, Schymkowitz J, Serrano L. 2006. Protein aggregation and amyloidosis: confusion of the kinds? Curr Opin Struct Biol. 16: 118–126. ArticlePubMed

- Salcedo-Sora JE, Kell DB. 2020. A quantitative survey of bacterial persistence in the presence of antibiotics: towards antipersister antimicrobial discovery. Antibiotics. 9: 508.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Samatova E, Daberger J, Liutkute M, Rodnina MV. 2021. Translational control by ribosome pausing in bacteria: how a non-uniform pace of translation affects protein production and folding. Front Microbiol. 11: 619430.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Sauer RT, Baker TA. 2011. AAA+ proteases: ATP-fueled machines of protein destruction. Annu Rev Biochem. 80: 587–612. ArticlePubMed

- Semanjski M, Grantani FL, Englert T, Nashier P, Beke V, et al. 2021. Proteome dynamics during antibiotic persistence and resuscitation. mSystems. 6: e00549-21.ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Serio AW, Keepers T, Andrews L, Krause KM. 2018. Aminoglycoside revival: review of a historically important class of antimicrobials undergoing rejuvenation. EcoSal Plus. 8: ESP-0002-2018.ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Silber N, Pan S, Schäkermann S, Mayer C, Brötz-Oesterhelt H, et al. 2020. Cell division protein FtsZ is unfolded for N-terminal degradation by antibiotic-activated ClpP. mBio. 11: e01006-20.ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Spanka DT, Konzer A, Edelmann D, Berghoff BA. 2019. High-throughput proteomics identifies proteins with importance to postantibiotic recovery in depolarized persister cells. Front Microbiol. 10: 378.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Stefan MA, Ugur FS, Garcia GA. 2018. Source of the fitness defect in rifamycin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis RNA polymerase and the mechanism of compensation by mutations in the β′ subunit. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 62: e00164-18.ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Stevens M, Howe C, Ray AM, Washburn A, Chitre S, et al. 2020. Analogs of nitrofuran antibiotics are potent GroEL/ES inhibitor pro-drugs. Bioorg Med Chem. 28: 115710.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Storey JM, Storey KB. 2023. Chaperone proteins: universal roles in surviving environmental stress. Cell Stress Chaperones. 28: 455–466. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Taylor G, Frommherz Y, Katikaridis P, Layer D, Sinning I, et al. 2022. Antibacterial peptide cyclomarin A creates toxicity by deregulating the Mycobacterium tuberculosis ClpC1-ClpP1P2 protease. J Biol Chem. 298: 102202.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Teichmann L, Luitwieler S, Bengtsson-Palme J, Ter Kuile B. 2025. Fluoroquinolone-specific resistance trajectories in E. coli and their dependence on the SOS-response. BMC Microbiol. 25: 37.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Telenti A, Imboden P, Marchesi F, Matter L, Schopfer K, et al. 1993. Detection of rifampicin-resistance mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Lancet. 341: 647–651. ArticlePubMed

- Thompson J, O’Connor M, Mills JA, Dahlberg AE. 2002. The protein synthesis inhibitors, oxazolidinones and chloramphenicol, cause extensive translational inaccuracy in vivo. J Mol Biol. 322: 273–279. ArticlePubMed

- Torrent M, Andreu D, Nogués VM, Boix E. 2011. Connecting peptide physicochemical and antimicrobial properties by a rational prediction model. PLoS One. 6: e16968. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Trentini DB, Suskiewicz MJ, Heuck A, Kurzbauer R, Deszcz L, et al. 2016. Arginine phosphorylation marks proteins for degradation by a Clp protease. Nature. 539: 48–53. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Van den Bergh B, Fauvart M, Michiels J. 2017. Formation, physiology, ecology, evolution and clinical importance of bacterial persisters. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 41: 219–251. ArticlePubMed

- Vasudevan D, Rao SPS, Noble CG. 2013. Structural basis of mycobacterial inhibition by cyclomarin A. J Biol Chem. 288: 30883–30891. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Vaubourgeix J, Lin G, Dhar N, Chenouard N, Jiang X, et al. 2015. Stressed mycobacteria use the chaperone ClpB to sequester irreversibly oxidized proteins asymmetrically within and between cells. Cell Host Microbe. 17: 178–190. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Wang Y, Tong Z, Han J, Li C, Chen X. 2025. Exploring novel antibiotics by targeting the GroEL/GroES chaperonin system. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 8: 10–20. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Wilson DN. 2014. Ribosome-targeting antibiotics and mechanisms of bacterial resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 12: 35–48. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Wilson DN, Beckmann R. 2011. The ribosomal tunnel as a functional environment for nascent polypeptide folding and translational stalling. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 21: 274–282. ArticlePubMed

- Won HI, Zinga S, Kandror O, Akopian T, Wolf ID, et al. 2024. Targeted protein degradation in mycobacteria uncovers antibacterial effects and potentiates antibiotic efficacy. Nat Commun. 15: 4065.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Wong F, Wilson S, Helbig R, Hegde S, Aftenieva O, et al. 2021. Understanding beta-lactam-induced lysis at the single-cell level. Front Microbiol. 12: 712007.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Xiao G, Cui Y, Zhou L, Niu C, Wang B, et al. 2025. Identification of a phenyl ester covalent inhibitor of caseinolytic protease and analysis of the ClpP1P2 inhibition in mycobacteria. mLife. 4: 155–168. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Zahn M, Kieslich B, Berthold N, Knappe D, Hoffmann R, et al. 2014. Structural identification of DnaK binding sites within bovine and sheep bactenecin Bac7. Protein Pept Lett. 21: 407–412. ArticlePubMed

- Zapun A, Contreras-Martel C, Vernet T. 2008. Penicillin-binding proteins and β-lactam resistance. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 32: 361–385. ArticlePubMed

References

Figure & Data

References

Citations

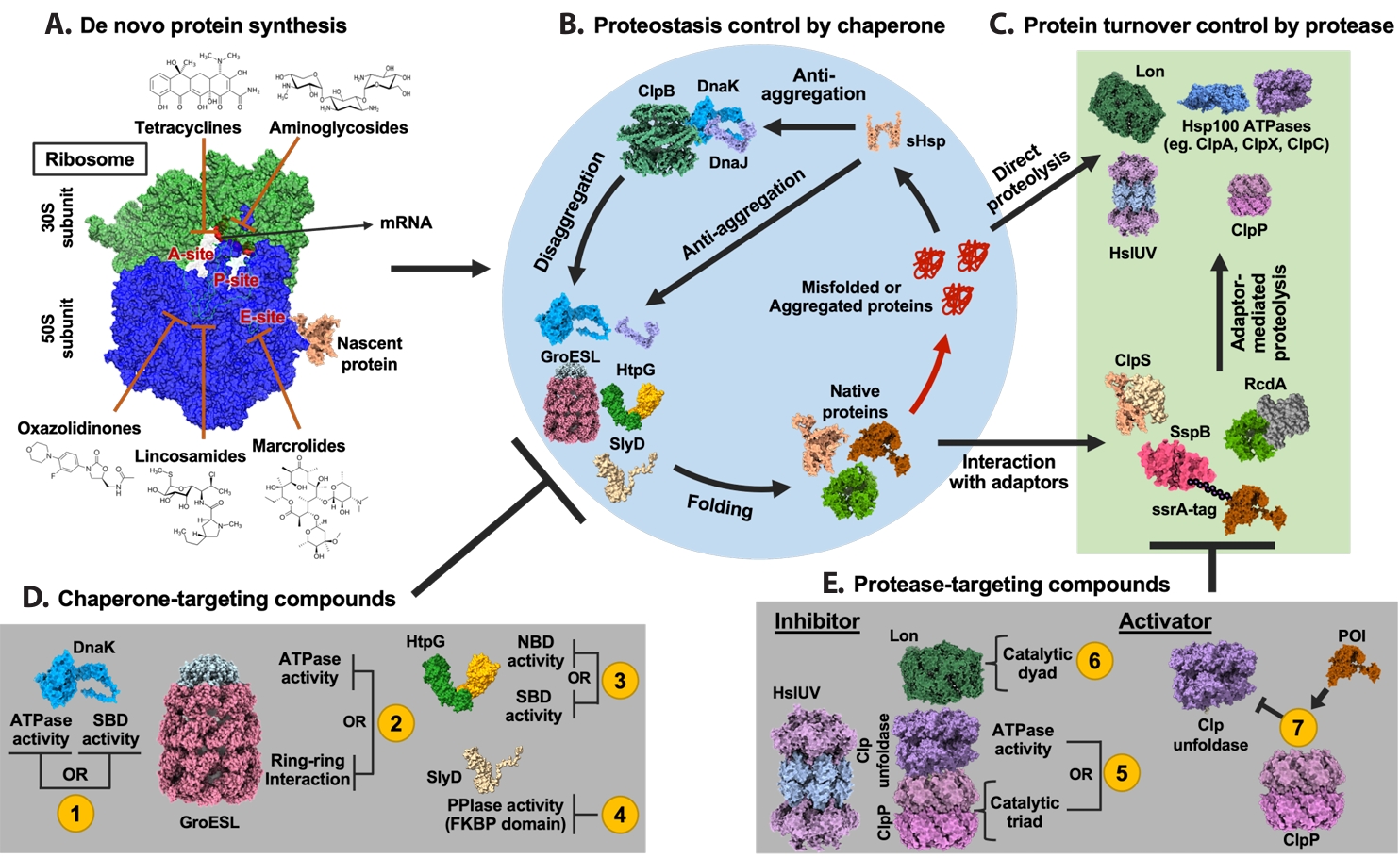

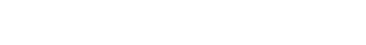

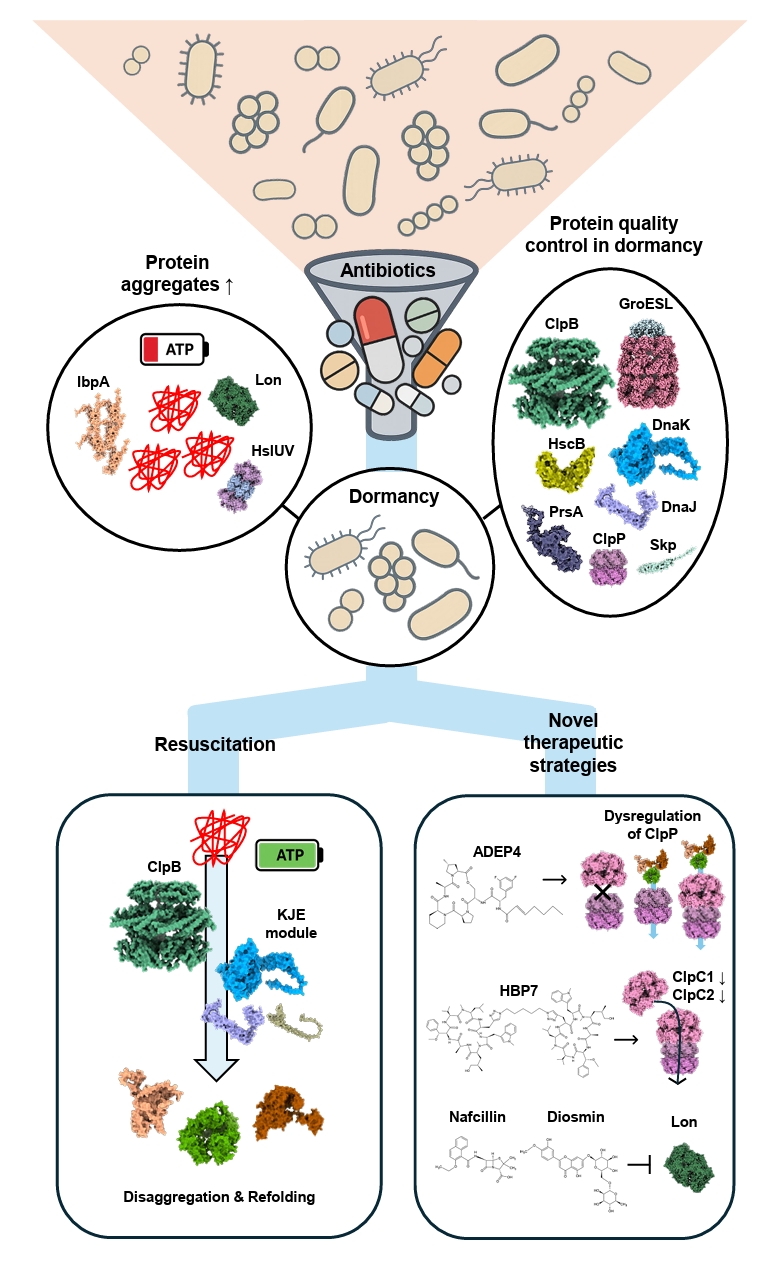

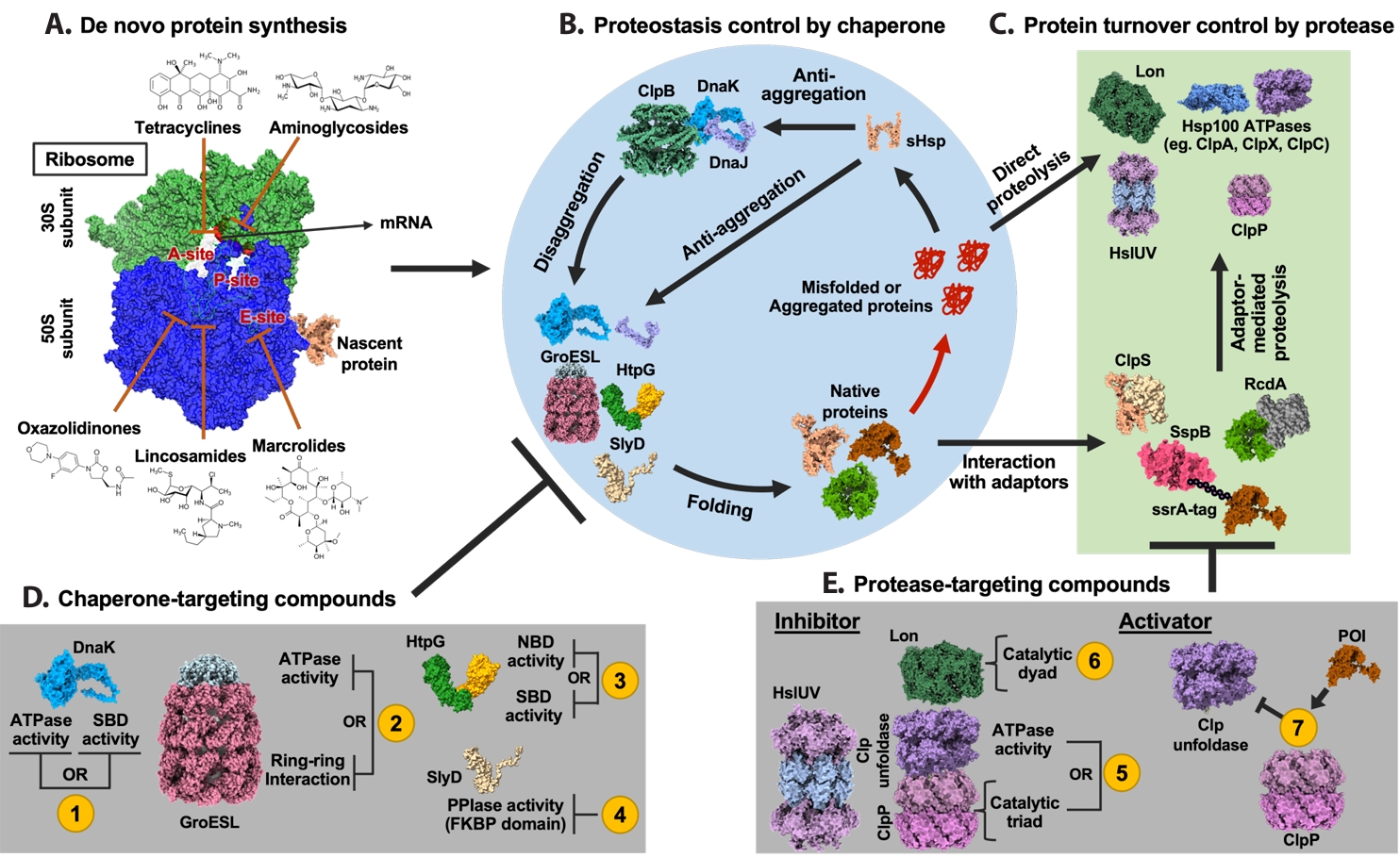

Fig. 1.

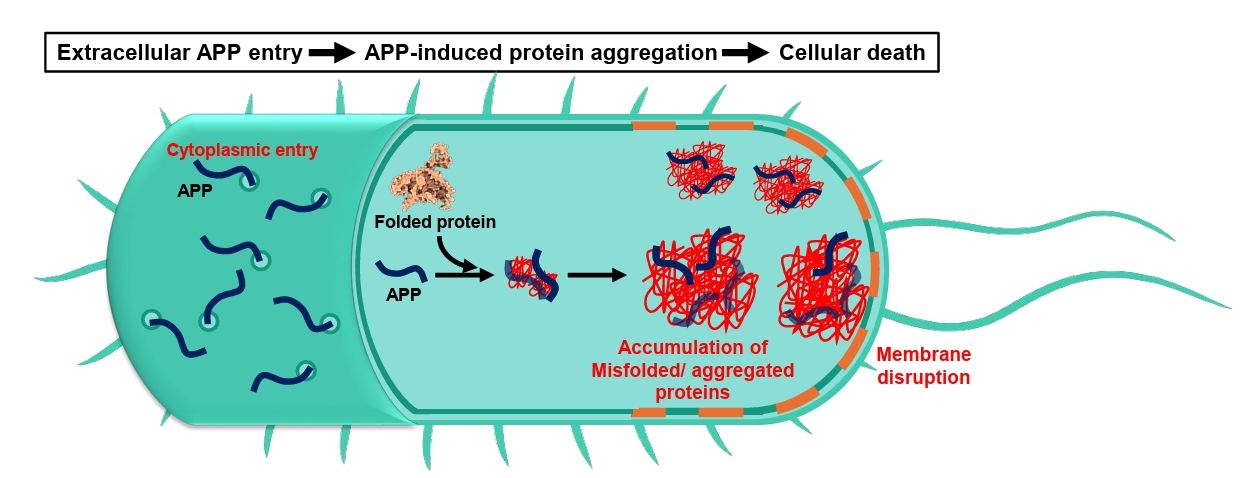

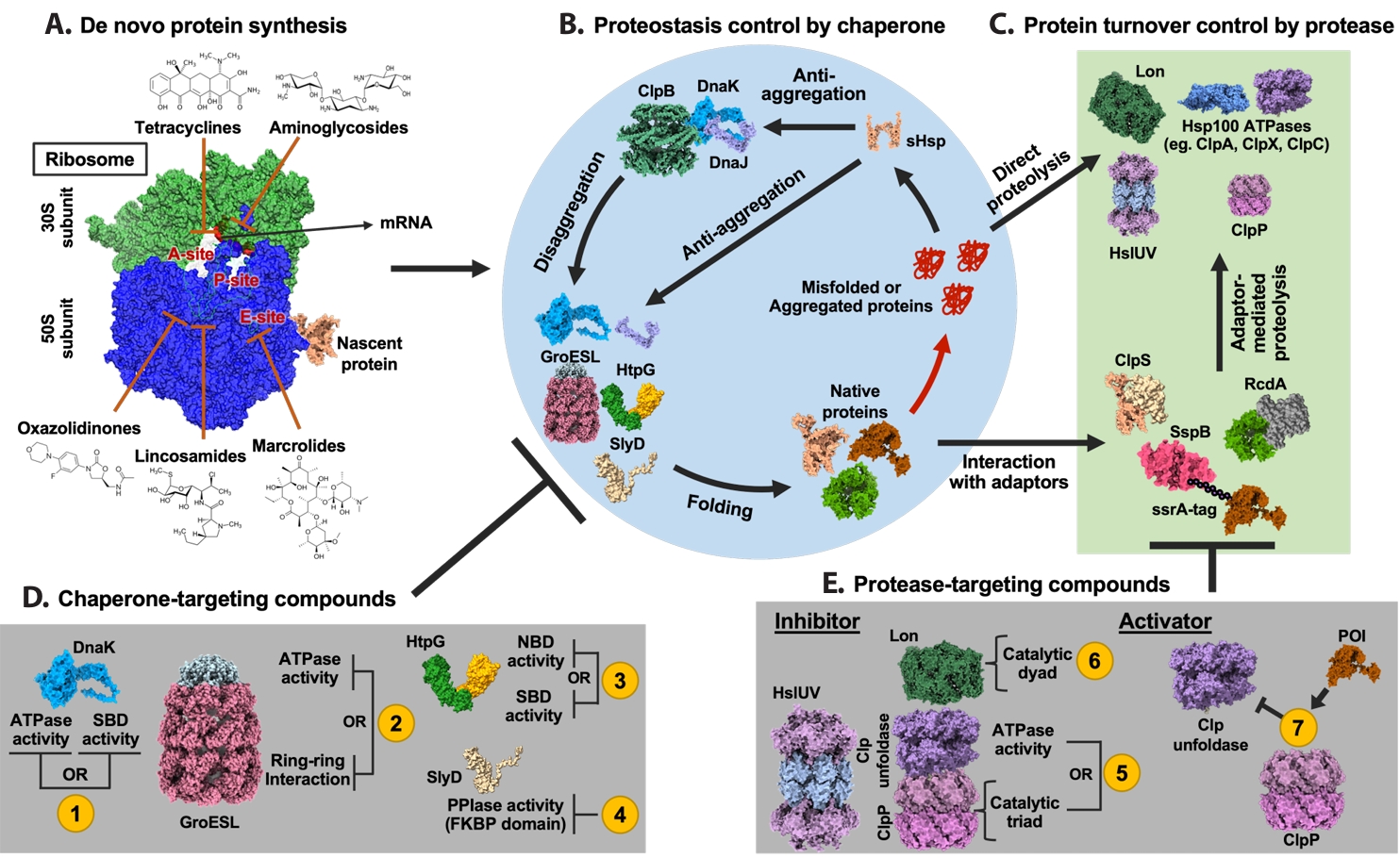

Fig. 2.

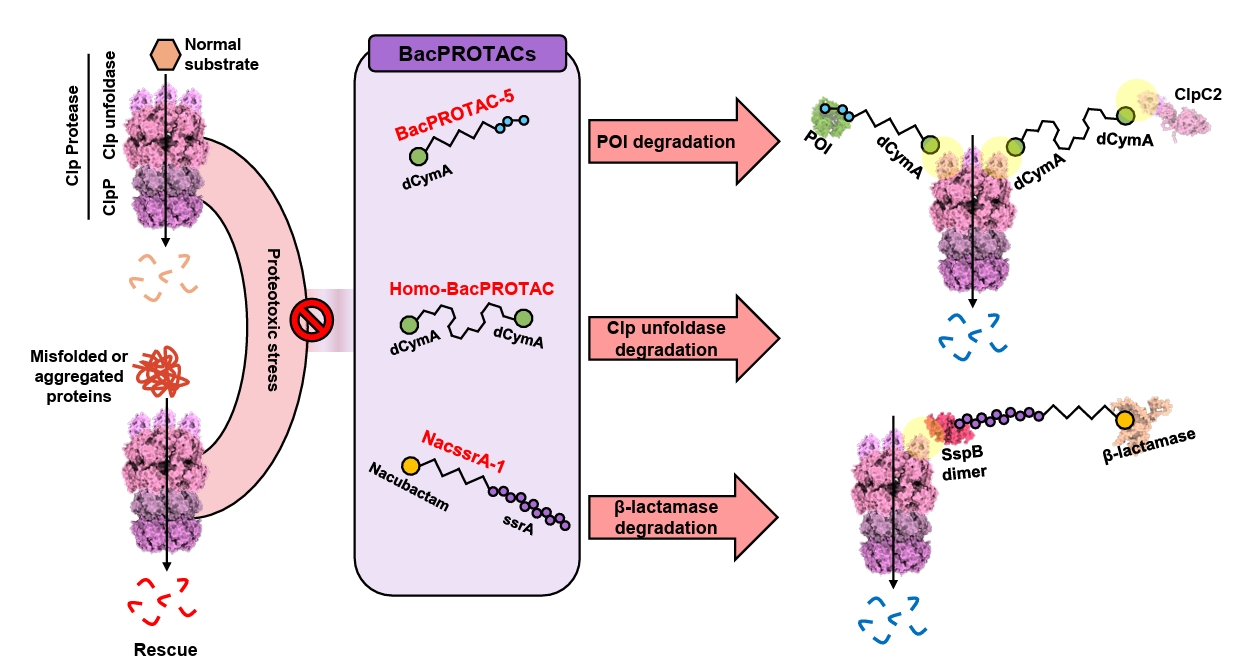

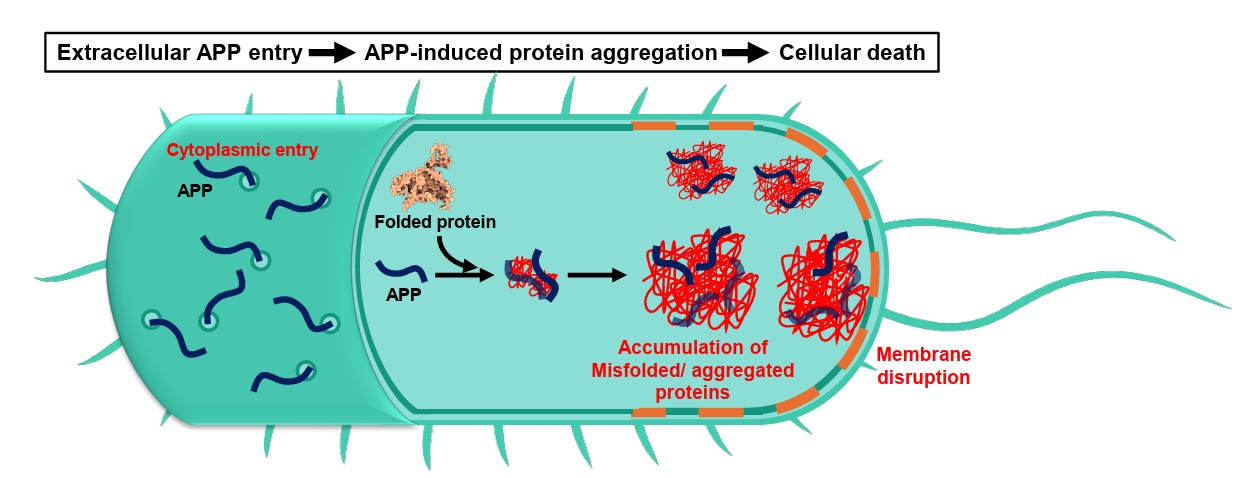

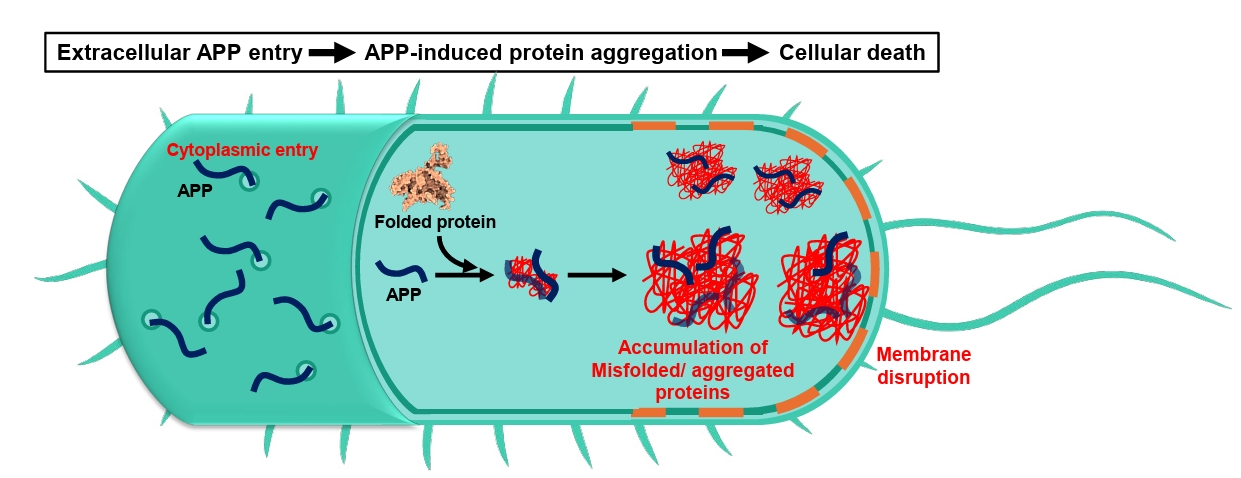

Fig. 3.

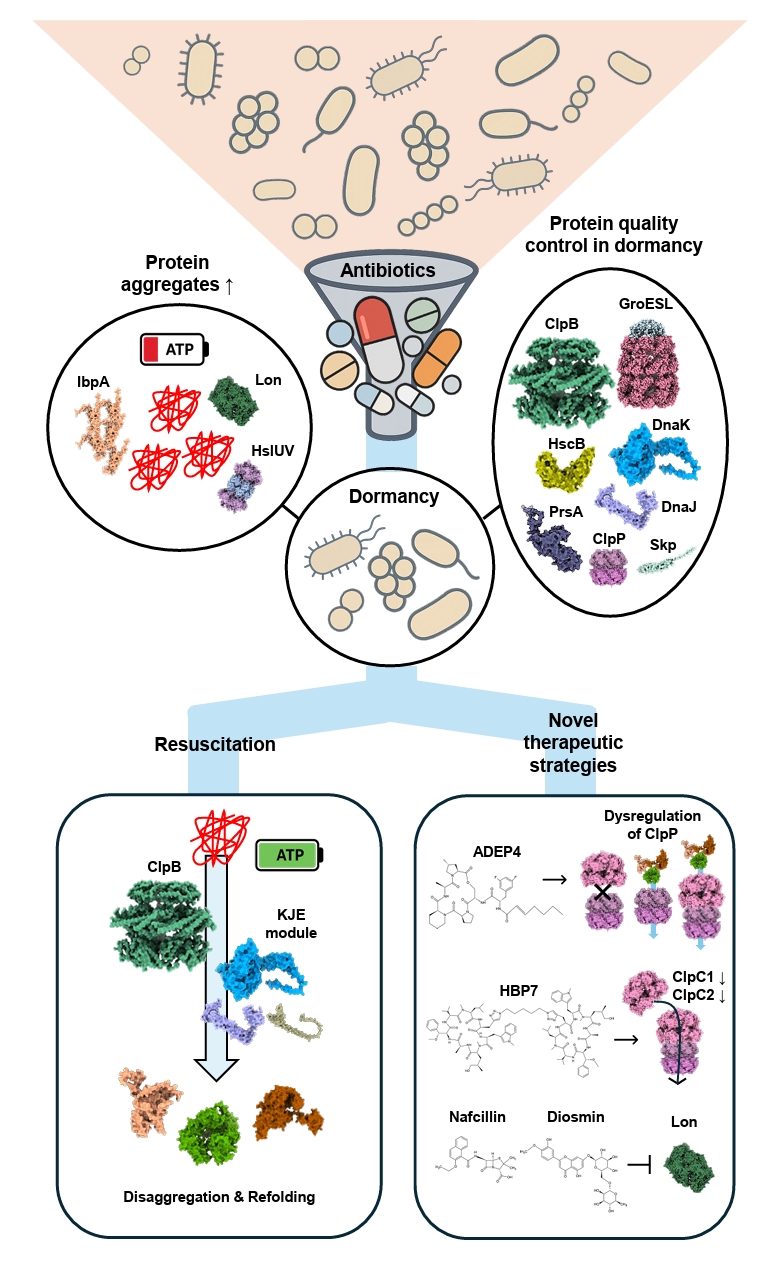

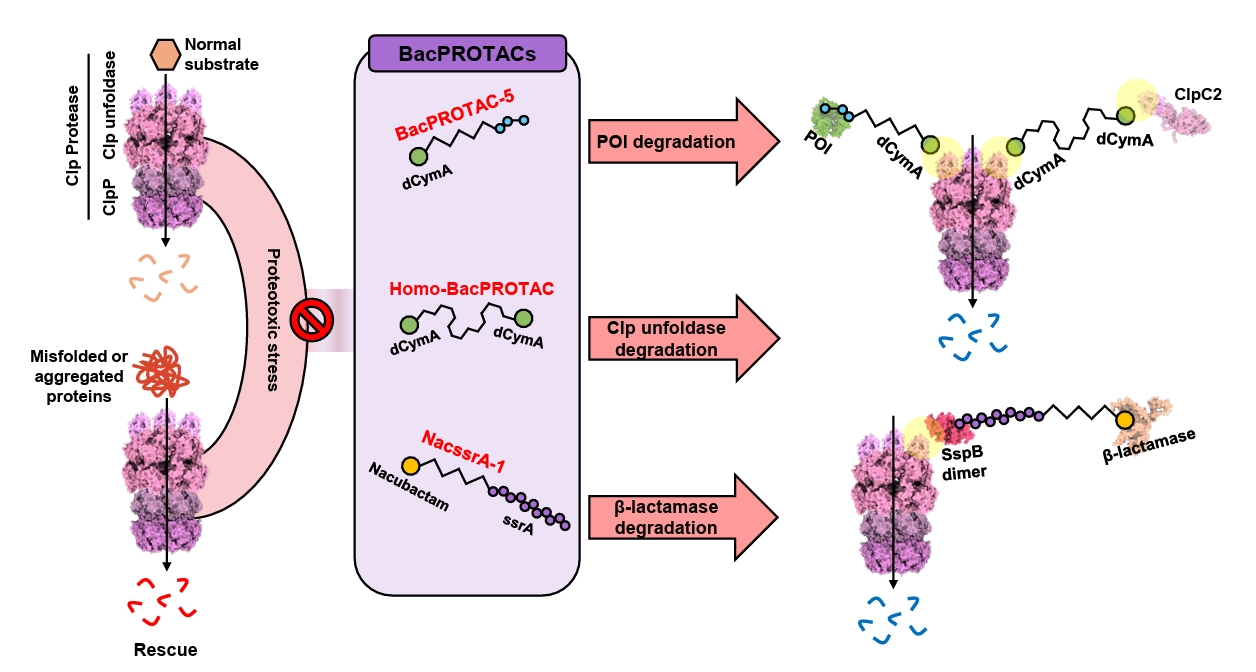

Fig. 4.

| Annotation in Fig. 1 | Name | Target sites | Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Telaprevir | SBD | Inhibit ATPase and chaperone activities of DnaK by disrupting allosteric coupling via substrate-mimicking interaction with the SBD | |

| BI-88E3 | SBD | Disrupt allosteric interaction within DnaK | ||

| BI-88D7 | ||||

| BI-88B12 | ||||

| Nα-[Tetradecanoyl-(4-aminomethylbenzoyl)]-l-isoleucine | SBD | Inhibit the DnaK-mediated catalysis of cis/trans isomerization | ||

| Drosocin | SBD and C-terminal region | Inhibit ATPase and chaperone activities of DnaK by disrupting allosteric coupling via substrate-mimicking interaction with the SBD | ||

| Pyrrhocoricin | ||||

| Apidaecin 1a | ||||

| Bac-7 | SBD | Impair DnaK-mediated refolding of denatured proteins | ||

| CHP-105 | Unknown | Synergistic effect with levofloxacin via DnaK inhibition | ||

| PET-16 | NBD | Bind to ADP-bound DnaK and inhibit DnaK-client interaction | ||

| 2 | Compound 8 | Unknown | Bactericidal activity against Escherichia coli | ( |

| Compound 18 | ||||

| Hydroxquinolines | Unknown | Inhibit GroEL/ES activity by binding to the apical domain via a noncanonical, non-hydrophobic interaction | ||

| Nifuroxazide | Apical domain | Inhibit the GroEL/ES folding cycle through apical domain binding | ||

| Bis-sulfonamido-2-phenylbenzoxazole | Apical domain | Inhibit ring-ring interaction of GroEL, compound derived from sulfonamido-2-arylbenzoxazole | ||

| Mizoribine | Equatorial domain | Inhibit ATPase activity of GroEL | ||

| 3 | BX-2819 | N-terminal domain (NTD) | Inhibit ATPase activity of HtpG | |

| HS-291 | BX-2819 derivative binds N-terminal ATP-binding pocket of HtpG, light-activated, triggers ROS generation | |||

| Polymixn B | Inhibit HtpG chaperone function without affecting its ATPase activity | |||

| 4 | Cu2+-anthracenyl terpyridine complex | FKBP domain | Inhibit SlyD PPIase activity | |

| 5 | β-Lactone | Active site serine in ClpP | Form covalent bond with the catalytic serine of ClpP and inhibit its proteolytic activity | |

| Phenyl esters | ||||

| Peptide boronic acids | ||||

| Clipibicyclene | ||||

| PCA | G107, V88, I81 in ClpP | Inhibit ClpP proteolytic activity | ||

| CA | M31, G33 in ClpP | Inhibit ClpP proteolytic activity by binding to active site residues M31 and G33 | ||

| Ameniaspirol | ClpXP, HslUV (ClpYQ) complex | Competitively inhibit ClpXP and HslUV (ClpYQ) | ||

| CymA | NTD of ClpC1 | Induce formation of large ClpC1 supercomplexes and activate associated ClpP protease via N-terminal domain binding | ||

| Lassomycin | Stimulate ClpC1 ATPase activity while inhibiting associated ClpP proteolytic activity | |||

| Ecumicin | Stimulate ClpC1 ATPase activity while inhibiting associated ClpP proteolytic activity | |||

| 6 | Nafcillin | Proteolytic active site | Interact with the binding pocket of Lon protease via hydrogen bonding; not reported as antibiotics | |

| Diosmin | ||||

| MG262 | Form covalent bond with catalytic serine of Lon protease and inhibit its proteolytic activity | |||

| Molecule 11 | Unknown | Inhibition of Lon protease proteolytic activity | ||

| 7 | ACP | Apical pocket | Enhance ClpP proteolytic activity independent of ATPase | |

| ADEP | Junction of the ClpP subunits | Bind to ClpP tetradecamer and enhance its proteolytic activity |

| Chaperone target | Representative inhibitors | Antibiotic partners | Model organism(s) | Reported effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DnaK/Hsp70 | Telaprevir (HCV protease inhibitor, repurposed) | Kanamycin, Streptomycin, Rifampicin | M. smegmatis, M. tuberculosis | Lowered MIC50 of aminoglycosides; reduced rifampicin resistance frequency; enhanced growth inhibition under heat/proteotoxic stress | |

| DnaK/Hsp70 | Proline-rich antimicrobial peptides (PrAMPs; e.g., pyrrhocoricin, synthetic dimers) | β-Lactams, Quinolones | E. coli, Salmonella spp. | Synergistic killing via disruption of DnaK folding function; accumulation of proteotoxic stress | |

| GroEL/ES | Hydroxybiphenylamide derivatives | Aminoglycosides (e.g., gentamicin) | Staphylococcus aureus | Impaired folding capacity; reduced biofilm survival; enhanced aminoglycoside bactericidal activity |

| Peptide ID | Target bacteria | Sequence feature | Aggregation morphology | Mammalian toxicity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C30 | MRSA | APR |

Amyloid-like | Low | |

| C29 | MRSA | APR + Arg flanks | Amyloid-like | Low | |

| Hit50 | MRSA | APR + Arg flanks | Amorphous inclusion bodies | Low | |

| Multiple APRs (263 tested) | S. aureus, E. faecalis, MRSA, Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus | Tandem APR repeats, charged gatekeepers | Amyloid and amorphous aggregation | Low |

APR; aggregation-prone region.

Table 1.

Table 2.

Table 3.

TOP

MSK

MSK

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite this Article

Cite this Article