Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J. Microbiol > Volume 63(12); 2025 > Article

-

Full article

Comparative genome analysis of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli ATCC 43894 and its pO157-cured strain 277 - Se Kye Kim1, Yong-Joon Cho2, Carolyn J. Hovde3, Sunwoo Hwang4, Jonghyun Kim4,*, Jang Won Yoon1,*

-

Journal of Microbiology 2025;63(12):e2511015.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71150/jm.2511015

Published online: December 31, 2025

1College of Veterinary Medicine & Institute of Veterinary Science, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon 24341, Republic of Korea

2Department of Molecular Bioscience, Multidimensional Genomics Research Center, College of Biomedical Science, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon 24341, Republic of Korea

3Department of Animal, Veterinary and Food Science, College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho 83844, USA

4Division of Zoonotic and Vector Borne Diseases Research, Center for Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Health, Cheongju 28159, Republic of Korea

-

*Correspondence Jonghyun Kim star5809@korea.kr

Jang Won Yoon jwy706@kangwon.ac.kr

© The Microbiological Society of Korea

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 830 Views

- 20 Download

ABSTRACT

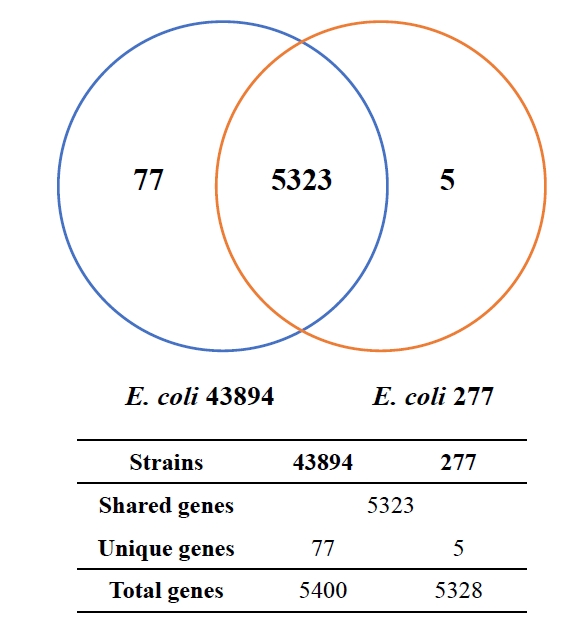

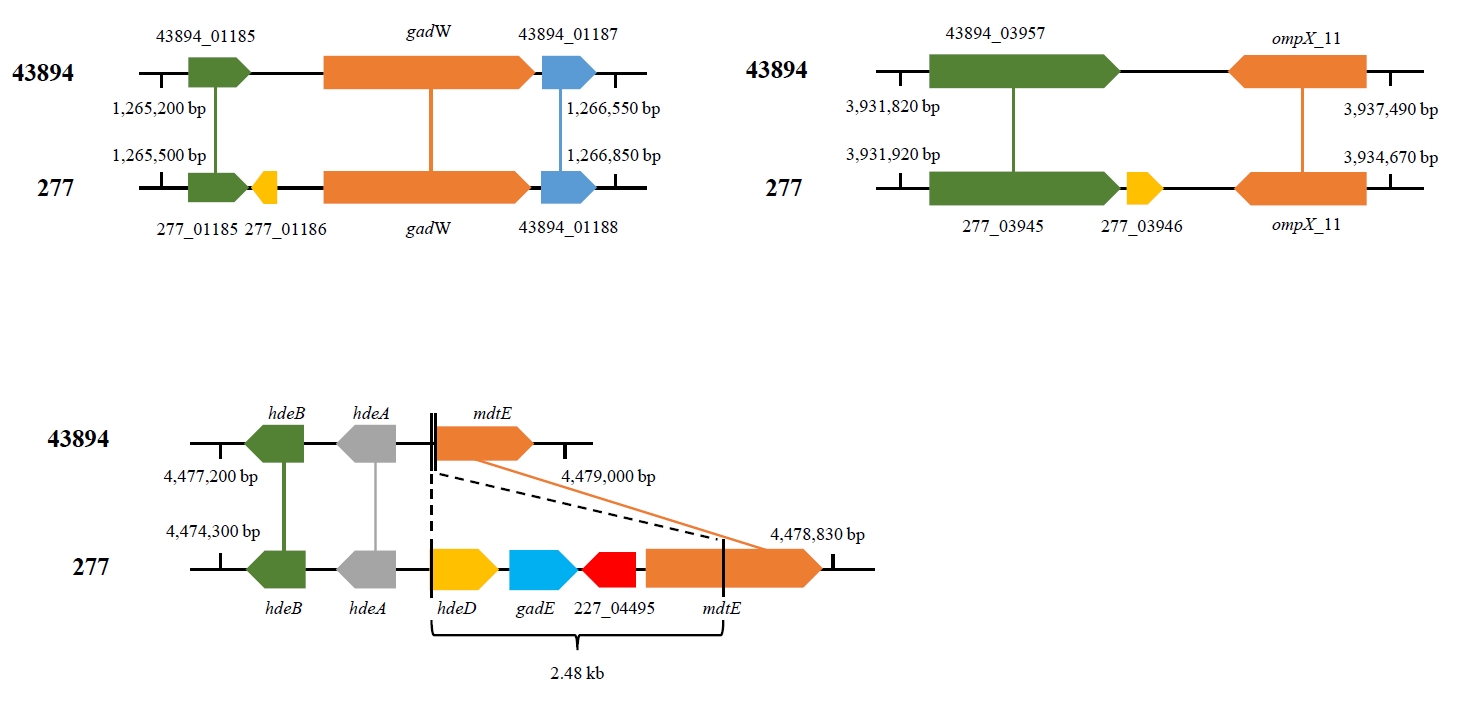

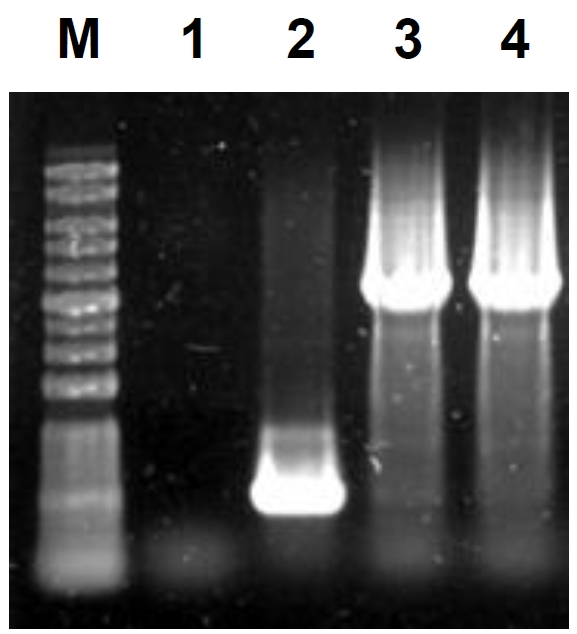

- Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) O157:H7 ATCC 43894 (also known as EDL932) has been widely used as a reference strain for studying the pathophysiology of EHEC. To elucidate the role of a large virulence plasmid pO157 and its relationship with acid resistance, for example, both EHEC ATCC 43894 and its pO157-cured derivative strain 277 were well studied. However, it is unclear whether or not these two strains are isogenic and share the same genetic background. To address this question, we analyzed the whole genome sequences of ATCC 43894 and 277. As expected, three and two closed contigs were identified from ATCC 43894 and 277, respectively; two contigs shared in both strains were a chromosome and a small un-identified plasmid, and one contig found only in ATCC 43894 was pO157. Surprisingly, our pan-genome analyses of the two sequences revealed several genetic variations including frameshift, substitution, and deletion mutations. In particular, the deletion mutation of hdeD and gadE in ATCC 43894 was identified, and further PCR analysis also confirmed their deletion of a 2.5-kb fragment harboring hdeD, gadE, and mdtE in ATCC 43894. Taken together, our findings demonstrate that EHEC ATCC 43894 harbors genetic mutations affecting glutamate-dependent acid resistance system and imply that the pO157-cured EHEC 277 may not be isogenic to ATCC 43894. This is the first report that such genetic differences between both reference strains of EHEC should be considered in future studies on pathogenic E. coli.

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Results

Discussion

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grants from the Animal & Plant Quarantine Agency (Z-1543081-2021-23-01), Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs, and from Research of Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2025-ER2101-00), Republic of Korea (J.W.Y). The research was also supported by a grant from the National Institute of Health (grant No. 2022-NI-020), Republic of Korea (J.H.K).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Supplementary Information

| 277 gene | Gene annotationb | 43894 contig/gene | Mutation | Sequence variationa | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 277_02321 | ORM96_01890 (phage portal gene) | 43894_02325 | Frameshift | c.544_545insA | |

| 43894 contig 1 | Frameshift | g.2314165_2314166insT | |||

| 43894_02324 | Frameshift | c.371_372insC | |||

| 43894_02323 | Frameshift | c.902_903insA | |||

| 277_02325 | ORM96_01910 (terminase small subunit) | 43894_02331 | Frameshift | c.390_391insC | Overlapping with 43894_02330 c.479_480insG |

| 43894_02330 | Frameshift | c.479_480insG | |||

| 277_02324 | ORM96_01905 (terminase large subunit) | 43894_02330 | Frameshift | c.56_57insA | |

| Frameshift | c.263_264insG | Overlapping with 43894_02331 c.390_391insC | |||

| 43894_02329 | Frameshift | c.403_404insT | Overlapping with 43894_02328 c.39_40insT | ||

| Substitution | c.488T > C | ||||

| Substitution | c.508A > C | ||||

| Substitution | c.519T > C | ||||

| Substitution | c.525A > G | ||||

| Substitution | c.541T > C | ||||

| Substitution | c.546G > T | ||||

| Substitution | c.558C > T | ||||

| Substitution | c.564G > C | ||||

| Substitution | c.573T > G | ||||

| Substitution | c.576G > T | ||||

| Substitution | c.606G > A | ||||

| Substitution | c.642T > C | ||||

| Substitution | c.666T > G | ||||

| Frameshift | c.946_947insC | ||||

| 277_02334 | ORM96_26320 (DUF1737 domain-containing protein) | 43894_02342 | Frameshift | c.584_585insG | |

| 43894_02341 | Frameshift | c.926_927insG | |||

| 277_02341 | ORM96_26280 (RusA family crossover junction endodeoxyribonuclease) | 43894_02349 | Frameshift | c.187delC | |

| 277_02340 | ORM96_26280 (bacteriophage antitermination protein Q) | 43894 contig 1 | Frameshift | g.2327535_2327536insG | |

| 43894 contig 1 | Frameshift | g.2327438delG | |||

| 277_02349 | ORM96_26240 (ATP-binding protein) | 43894_02359 | Frameshift | c.210_211insT | |

| 43894 contig 1 | Frameshift | g.2332332_2332333insG | |||

| 277_02350 | ORM96_26235 (helix-turn-helix domain-containing protein) | 43894_02362 | Frameshift | c.274_275insA | Overlapping with 43894_02361 c.6_7insA |

| 43894_02361 | Frameshift | c.6_7insA | Overlapping with 43894_02362 c.274_275insA | ||

| Frameshift | c.285delT | ||||

| 43894 contig 1 | Frameshift | g.2332991_2332992insC | |||

| 43894_02360 | Frameshift | c.35_36insG |

- An YW, Choi YS, Yun MR, Choi C, Kim SY. 2022. Characterization and validation of an alternative reference bacterium Korean Pharmacopoeia Staphylococcus aureus strain. J Microbiol. 60: 187–191. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Edwards K, Linetsky I, Hueser C, Eisenstark A. 2001. Genetic variability among archival cultures of Salmonella typhimurium. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 199: 215–219. ArticlePubMed

- Kailasan Vanaja S, Bergholz TM, Whittam TS. 2009. Characterization of the Escherichia coli O157:H7 Sakai gadE regulon. J Bacteriol. 191: 1868–1877. ArticlePubMedLink

- Kim SK, Lee JB, Yoon JW. 2022. Characterization of transcriptional activities at a divergent promoter of the type VI secretion system in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. J Microbiol. 60: 928–934. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Lee MS, Kim MH, Tesh VL. 2013. Shiga toxins expressed by human pathogenic bacteria induce immune responses in host cells. J Microbiol. 51: 724–730. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Lee KS, Park JY, Jeong YJ, Lee MS. 2023. The fatal role of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli shiga toxin-associated extracellular vesicles in host cells. J Microbiol. 61: 715–727. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Lim JY, La HJ, Sheng H, Forney LJ, Hovde CJ. 2010. Influence of plasmid pO157 on Escherichia coli O157:H7 Sakai biofilm formation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 76: 963–966. ArticlePubMedLink

- Lim JY, Sheng H, Seo KS, Park YH, Hovde CJ. 2007. Characterization of an Escherichia coli O157:H7 plasmid O157 deletion mutant and its survival and persistence in cattle. Appl Environ Microbiol. 73: 2037–2047. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Liu GR, Edwards K, Eisenstark A, Fu YM, Liu WQ, et al. 2003. Genomic diversification among archival strains of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT7. J Bacteriol. 185: 2131–2142. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Seemann T. 2014. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 30: 2068–2069. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Sprouffske K, Aguilar-Rodríguez J, Wagner A. 2016. How archiving by freezing affects the genome-scale diversity of Escherichia coli populations. Genome Biol Evol. 8: 1290–1298. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Tatsuno I, Horie M, Abe H, Miki T, Makino K, et al. 2001. toxB gene on pO157 of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 is required for full epithelial cell adherence phenotype. Infect Immun. 69: 6660–6669. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Uhlich GA, Chen CY, Cottrell BJ, Hofmann CS, Dudley EG, et al. 2013. Phage insertion in mlrA and variations in rpoS limit curli expression and biofilm formation in Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7. Microbiology. 159: 1586–1596. ArticlePubMed

- Uhlich GA, Paoli GC, Chen CY, Cottrell BJ, Zhang X, et al. 2016. Whole-genome sequence of Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7 strain EDL932 (ATCC 43894). Genome Announc. 4: e00647-16.ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Walker BJ, Abeel T, Shea T, Priest M, Abouelliel A, et al. 2014. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One. 9: e112963.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Wells JG, Davis BR, Wachsmuth IK, Riley LW, Remis RS, et al. 1983. Laboratory investigation of hemorrhagic colitis outbreaks associated with a rare Escherichia coli serotype. J Clin Microbiol. 18: 512–520. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Wi SM, Kim SK, Lee JB, Yoon JW. 2023. Acid tolerance of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain ATCC 43894 and its relationship with a large virulence plasmid pO157. Vet Microbiol. 284: 109833.ArticlePubMed

- Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, Holt KE. 2017. Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput Biol. 13: e1005595.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Youn M, Lee KM, Kim SH, Lim J, Yoon JW, et al. 2013. Escherichia coli O157:H7 LPS O-side chains and pO157 are required for killing Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 436: 388–393. ArticlePubMed

- Yun S, Min J, Han S, Sim HS, Kim SK, et al. 2024. Experimental evolution under different nutritional conditions changes the genomic architecture and virulence of Acinetobacter baumannii. Commun Biol. 7: 1274.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

References

Figure & Data

References

Citations

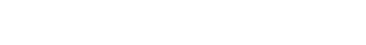

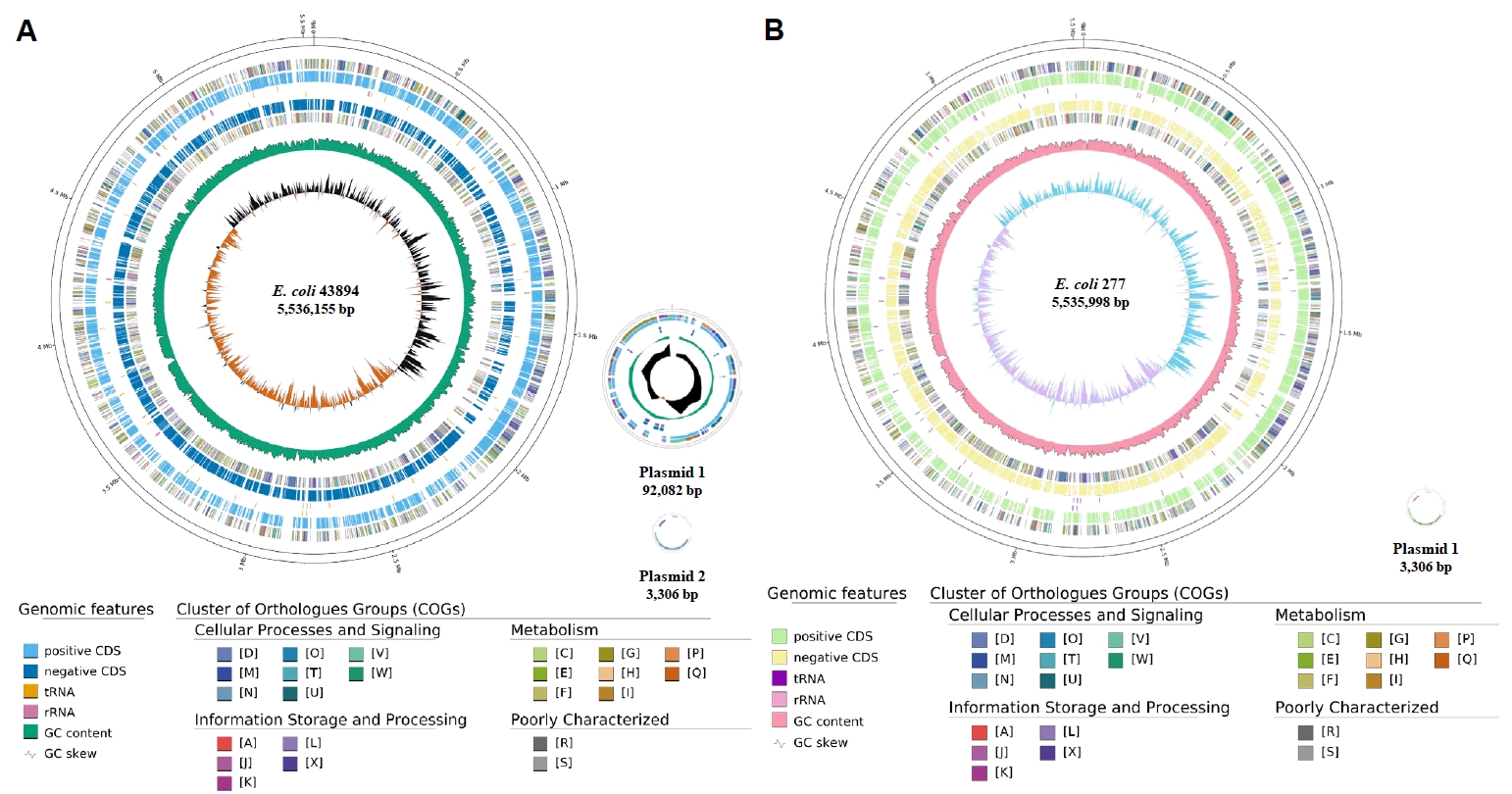

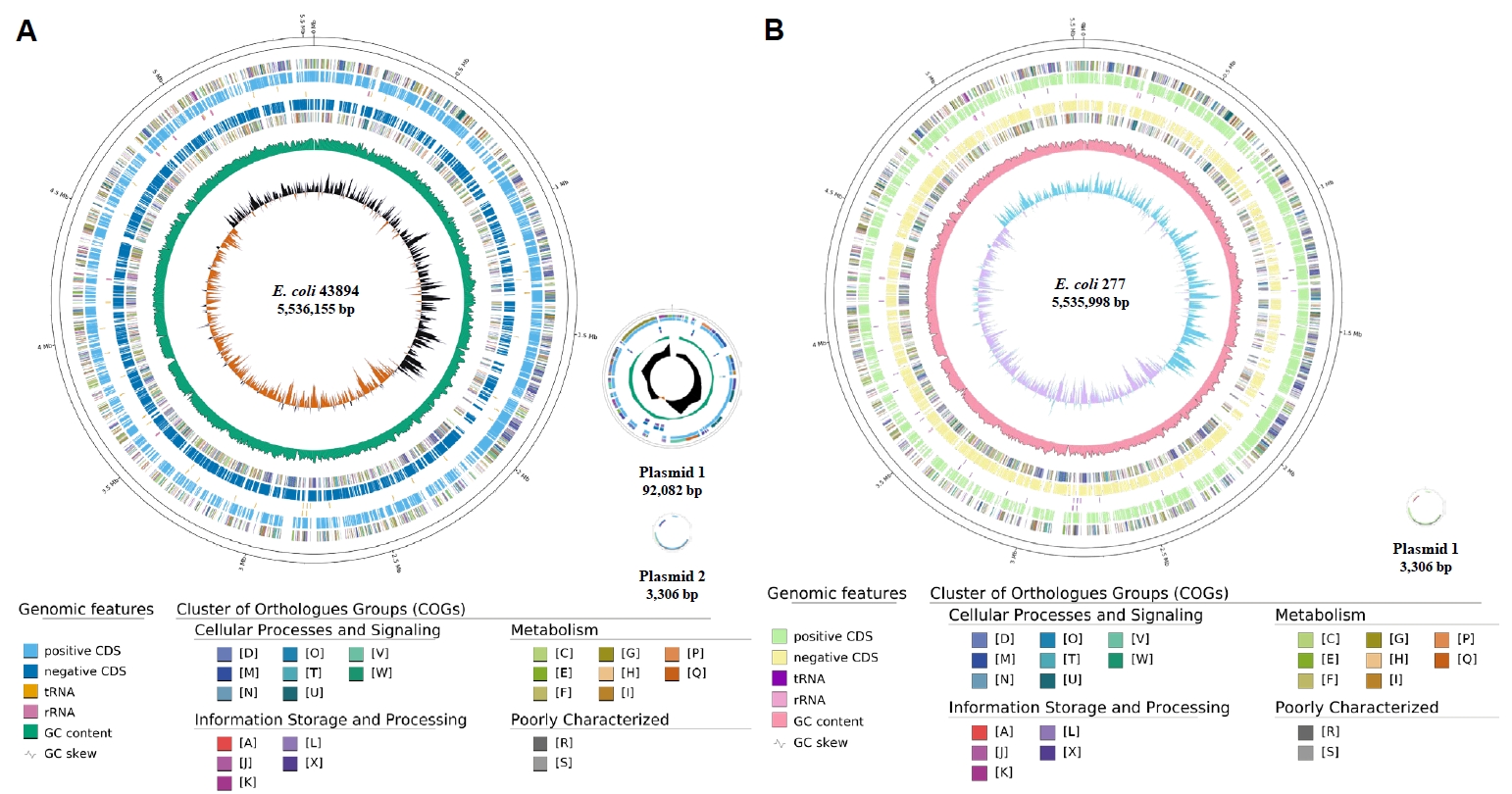

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.

| 277 gene | Gene annotation |

43894 contig/gene | Mutation | Sequence variation |

Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 277_02321 | ORM96_01890 (phage portal gene) | 43894_02325 | Frameshift | c.544_545insA | |

| 43894 contig 1 | Frameshift | g.2314165_2314166insT | |||

| 43894_02324 | Frameshift | c.371_372insC | |||

| 43894_02323 | Frameshift | c.902_903insA | |||

| 277_02325 | ORM96_01910 (terminase small subunit) | 43894_02331 | Frameshift | c.390_391insC | Overlapping with 43894_02330 c.479_480insG |

| 43894_02330 | Frameshift | c.479_480insG | |||

| 277_02324 | ORM96_01905 (terminase large subunit) | 43894_02330 | Frameshift | c.56_57insA | |

| Frameshift | c.263_264insG | Overlapping with 43894_02331 c.390_391insC | |||

| 43894_02329 | Frameshift | c.403_404insT | Overlapping with 43894_02328 c.39_40insT | ||

| Substitution | c.488T > C | ||||

| Substitution | c.508A > C | ||||

| Substitution | c.519T > C | ||||

| Substitution | c.525A > G | ||||

| Substitution | c.541T > C | ||||

| Substitution | c.546G > T | ||||

| Substitution | c.558C > T | ||||

| Substitution | c.564G > C | ||||

| Substitution | c.573T > G | ||||

| Substitution | c.576G > T | ||||

| Substitution | c.606G > A | ||||

| Substitution | c.642T > C | ||||

| Substitution | c.666T > G | ||||

| Frameshift | c.946_947insC | ||||

| 277_02334 | ORM96_26320 (DUF1737 domain-containing protein) | 43894_02342 | Frameshift | c.584_585insG | |

| 43894_02341 | Frameshift | c.926_927insG | |||

| 277_02341 | ORM96_26280 (RusA family crossover junction endodeoxyribonuclease) | 43894_02349 | Frameshift | c.187delC | |

| 277_02340 | ORM96_26280 (bacteriophage antitermination protein Q) | 43894 contig 1 | Frameshift | g.2327535_2327536insG | |

| 43894 contig 1 | Frameshift | g.2327438delG | |||

| 277_02349 | ORM96_26240 (ATP-binding protein) | 43894_02359 | Frameshift | c.210_211insT | |

| 43894 contig 1 | Frameshift | g.2332332_2332333insG | |||

| 277_02350 | ORM96_26235 (helix-turn-helix domain-containing protein) | 43894_02362 | Frameshift | c.274_275insA | Overlapping with 43894_02361 c.6_7insA |

| 43894_02361 | Frameshift | c.6_7insA | Overlapping with 43894_02362 c.274_275insA | ||

| Frameshift | c.285delT | ||||

| 43894 contig 1 | Frameshift | g.2332991_2332992insC | |||

| 43894_02360 | Frameshift | c.35_36insG |

Genetic mutations and their locations denoted as follows: c, coding sequence; g, genomic DNA; ins, insertion; del, deletion; >, nucleotide substitution. Annotated using BLASTn against

Table 1.

TOP

MSK

MSK

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite this Article

Cite this Article